Scroll to:

Caesarean section through the prism of fine art and mythological stories

https://doi.org/10.17749/2313-7347/ob.gyn.rep.2024.558

Abstract

Caesarean section is one of the ancient and most outstanding operations, with roots going deep into the past. It shows unmatched significance in that it is the only operation responsible for the lives of two people – mother and child. Hypotheses about the origin of the term a Сaesarean section, the history of its development and methods underlying execution the operation are discussed here. The article highlights issues aimed at Сaesarean section in fine art, the historical stages of this operation and their reflection in fine arts. Studying artistic works related to Caesarean section helps us to better understand its impact on mankind and social consciousness.

For citations:

Matveeva N.V., Makatsariya N.A. Caesarean section through the prism of fine art and mythological stories. Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproduction. 2024;18(5):761–768. https://doi.org/10.17749/2313-7347/ob.gyn.rep.2024.558

Introduction / Введение

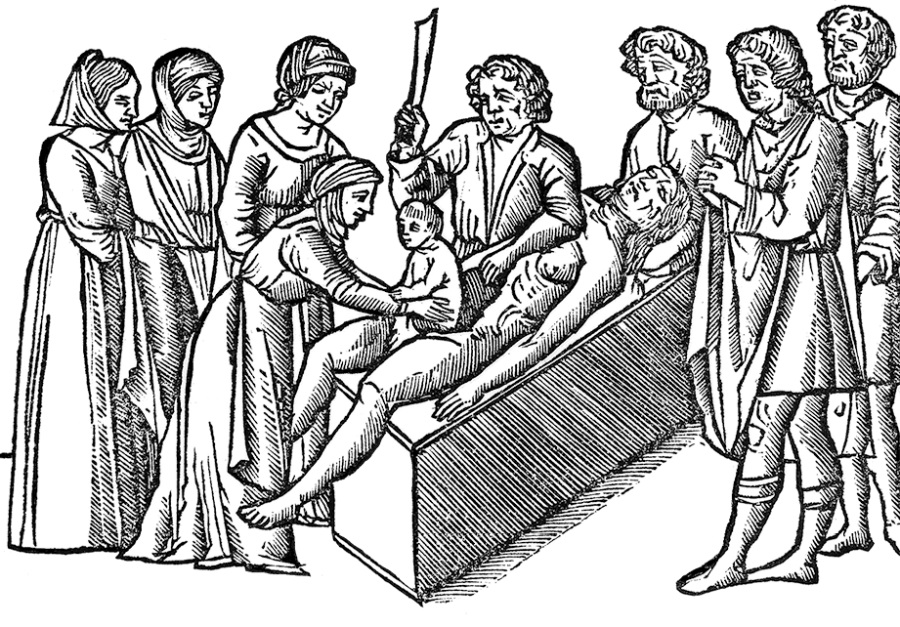

The line dividing life and death has always been a battlefield for the highest values of humanism. One of such literal lines of division and at the same time a humanity’s achievement in the battle with fate is the Caesarean section. Whereas Caesarean section was something unnatural, scary, burdened with death in the Middle Ages, it seems that the heroes are asking God whether this child will be accepted on earth, whether the higher powers will allow it to remain alive in this world, then over time the question of life and death becomes far from primary in symbolic readings. Other difficulties, other problems are revealed, but not terrifying chthonic awe in the face of the universe and a prospect of possible punishment. Thus in a medieval engraving, a midwife, extracting a child, presents it to the divine gaze, as if she were calling out with a request for permission to be, or perhaps to be under the care of the Great Father (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Medieval engraving.

Рисунок 1. Средневековая гравюра.

Shakespeare in his play "Macbeth" describes the hero with the following words: "Tell thee, Macduff was from his mother's womb untimely ripp'd" [1], emphasizing the unnaturalness and painfulness of action and phenomenon. And the plot of the play itself reports that a heavy mission is imposed on the child "torn out with a knife".

A human hand intruding into processes controlled by nature caused fear in front of higher powers and was associated not only with saving a life, but also with mortal punishment. It is not surprising that the tone of the narrative in such stories was so gloomy, because for many centuries this operation was performed only on dead women.

Background / Краткая история вопроса

There are several hypotheses about the origin of the term "caesarean section", and the most probable of them is the following. In 715 BC, the Roman king Numa Pompilius issued the Lex Regia law, according to which it was forbidden to bury a pregnant woman without removing a child from her belly, even in case of minimal chance for a child’s survival. This was done so that mother and child were buried separately, in different graves (Fig. 2). And later this law was renamed Lex Caesarea in emperor’s honor.

Figure 2. From "Suetonius' Lives of the Twelve Caesars", 1506. One of the earliest engravings illustrating a Caesarean section performed on a deceased woman. A living baby is surgically removed from a deceased woman’s body.

Рисунок 2. Из «Жизнеописания двенадцати цезарей» Светония, 1506 г. Одна из самых ранних гравюр, иллюстрирующая проведение операции кесарева сечения умершей женщине. Живого младенца хирургическим путем извлекают из тела умершей женщины.

A timeline of developing the Caesarean section is divided into three main stages. The first stage dates back to the period before 1500, when operations were mainly performed posthumously in order to save a child or to bury mother and child in separate graves for religious reasons (Fig. 3). The second stage includes the years spanning from 1500 to 1876. It is known that in 1500 the first successful operation was performed on a living woman. The third stage begins in 1876, which, thanks to the research by Eduardo Porro and Max Sanger is considered the beginning of contemporary Caesarean section technique.

Figure 3. Caesarean section, circa 1420. Illustration from a 15th-century gynecological text.

Рисунок 3. Кесарево сечение, около 1420 г. Иллюстрация из гинекологического текста XV века.

There is a hypothesis that King Robert II of Scotland was born by Caesarean section. George Craufurd in his book “The History of the County of Renfrewshire” (1710) recounts that on March 2, 1316, Robert's pregnant mother was returning from service at Paisley Abbey when she fell from her horse and sustained fatal injuries. Sir John Forrester, who was accompanying her and had some surgical skills, immediately assessed the situation and, being eager to save a child, he performed Caesarean section. The baby was born alive. Another royal person possibly born by Caesarean section is Edward VI, the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour (born October 12, 1537) [2], as evidenced by numerous works.

In 1500, a significant event in the history of developing Caesarean section occurred: for the first time, the operation was successfully performed on a living woman. Until that time, the operation was performed solely on deceased mothers (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Figure XLII from Armamentaerium chirugicum bipartum by I. Skultet, 1666. Pamphlet for the exhibition on the history of Caesarean section at the National Library of Medicine, April 30–August 31, 1993.

Рисунок 4. Рисунок XLII из Armamentaerium chirugicum bipartum И. Скультета, 1666 г. Брошюра к выставке по истории кесарева сечения в Национальной медицинской библиотеке, 30 апреля – 31 августа 1993 г.

The story of the first Caesarean section on a living woman is described as follows. The wife of the Swiss veterinarian Jacob Nufer could not give birth naturally for unknown reasons. Thirteen midwives tried to help, but to no avail. The worried husband called a doctor who was also unable to help. In desperation, Jacob Nufer asked the mayor for permission to perform a Сaesarean section, and only on the second attempt he received it. Despite great anxiety, Jacob personally performed successful operation, and his wife recovered, later to give a natural birth to five more children.

The French surgeon Ambroise Paré (1510–1590) published his book on surgery (1579), in which he sharply criticized the Caesarean section. He considered it extremely dangerous and doubted the possibility of subsequent pregnancies and natural births. Nevertheless, he described one reliable case of a successful Caesarean section [3].

The book by the French obstetrician François Morisot (1637–1709) played an important role in the history of Caesarean section. It was one of the best works on obstetrics of that time, in which the tactics of managing pregnant women under normal conditions and with various obstetric pathologies were examined in detail [4][5].

The outstanding book on obstetrics of that time by William Smellie (the "Father of British obstetrics") was published in 1752 and called "A Treatise of the Theory and Practice of Midwifery". Regarding Сaesarean section, Smellie believed that in cases where natural childbirth was impossible, it was better to perform the operation than to wait for death of both mother and child. However, Smellie performed only three Сaesarean sections, all after women died from bleeding, and in all three cases, unfortunately, the children were stillborn [6][7].

Another landmark book was the work by Jean Louis Baudelocque (1746-1810), who detailed the technique of Сaesarean section and assessed a relationship between fetal head and pelvis sizes. In another book, Baudelocque analyzed several cases of such operation by identifying its shortcomings and possible causes of failure. Mortality was mainly related to delay in performing the operation [8][9].

An extremely important stage in the development of Caesarean section is the Porro operation, as it allowed to significantly reduce postoperative mortality. For this reason, Eduardo Porro is a pioneer in this field and can be considered one of the founding fathers of contemporary operative obstetrics. He proposed performing a hysterectomy as the final stage of Caesarean section. However, one of the serious disadvantages of the operation was that it led to women’s sterilization [10][11].

In 1882, Max Sanger, a German surgeon, proposed a new method of performing a Caesarean section that profoundly changed the approach to operative obstetrics. This method, known as the Sanger operation or conservative Caesarean section, differed from previous techniques by placing a double-row suture on the uterus. The technique ensured a secure hemostasis, reduced peritonitis risk and allowed to preserve uterus.

In the following years, obstetricians focused on the methods of performing uterine incisions. Between 1880 and 1925, several variants of transverse incisions were proposed. The best results were achieved using a transverse incision in the lower segment of the uterus, which reduced the risk of infectious complications and uterine ruptures during subsequent pregnancies. And, of course, it is impossible not to mention the names of scientists whose discoveries led to new achievements in surgery and particularly in obstetrics. These are the discoveries of asepsis and antisepsis by Joseph Lister, before whom Ignaz Semmelweis played a huge role in the field, the discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming in 1928, whereas its introduction as a drug into practice in the 1940s led to a markedly decreased infectious complications, including post-Caesarean section.

Evolution of Caesarean section perceptions in fine art and myths / Эволюция восприятия кесарева сечения в изобразительном искусстве и мифах

Early references to Caesarean sections are described in a more horrific form. For instance, a mythological story tells about the birth of Asclepius, the god of healing. According to one of the most disturbing versions, Coronis became pregnant by Apollo and cheated on him with the mortal Ischys. Having known of this, Apollo, in a rage, shot Coronis with arrows, and on her funeral pyre, he took the child out of her womb and gave it to the centaur Chiron to raise (Fig. 5, 6).

Figure 5. The extraction of Asclepius by Father Apollo from the womb of his mother Coronis. Woodcut from Alessandro Beneditti's book "De Re Medica", 1549.

Рисунок 5. Извлечение Асклепия отцом Аполлоном из чрева его матери Корониды. Гравюра на дереве из книги Алессандро Бенедитти «De Re Medica», 1549 г.

Figure 6. Apollo and Coronis.

Рисунок 6. Аполлон и Коронида.

Dionysus, the god of wine in Greek mythology, is believed to have been the son of Zeus and Semele. When Zeus' wife Hera learned that Semele was pregnant, she was furious and decided to destroy Semele. Hera inspired Semele with desire to see Zeus in all his divine glory. When Zeus appeared in front of Semele, she demanded to grant her any wish. Semele asked him to embrace her as he would have embraced Hera. Zeus, forced to fulfill her request, appeared before her in a fiery flash of lightning, and Semele was instantly engulfed in flames. Zeus managed to extract a premature baby from her womb and sew it into his thigh (Fig. 7, 8).

Figure 7. Bon de Boulogne. Semele, between 1688 and 1704.

Рисунок 7. Бон де Булонь. Семела, между 1688 и 1704 гг.

Figure 8. Francesco Podesti. Birth of Dionysus, 19th century.

Рисунок 8. Франческо Подести. Рождение Диониса, XIX век.

The archetypal level of such stories can be interpreted in many ways. But a connection between extraction of a child and inevitability of mother's death long remained on the surface of the reading.

The origin of Buddha in the middle of the 6th century BC is also associated with a Caesarean section. In later biographies, a story appears about miraculous conception of Buddha, according to which Mayadevi (Buddha's mother) in a dream sees a white elephant with six tusks entering her side, as well as the prediction of the sage Asita about the great future for the baby to become either a great king or a great sage. Then there appears a legend about the pure birth of Buddha from his mother's side in the Lumbini grove (Fig. 9). It also mentions Mayadevi's death during childbirth.

Figure 9. Life of Buddha Thangka.

Рисунок 9. Жизнь Будды Тханка.

The mother of Rustam, the legendary hero of the Persian folk epic, survived a Caesarean section. According to the legend, the magical bird Simurg advised the birth to be done by Caesarean section because of the enormous child’s size. After Rustam was extracted, the wound was carefully stitched and healed soon (Fig. 10).

Figure 10. Scene from Shahnameh: Birth of Rustam, 1616. Mughal, India.

Рисунок 10. Сцена из Шахнаме: рождение Рустама, 1616 г. Могол, Индия.

Enrique Grau's painting of a Caesarean section (Fig. 11) is a dramatic and touching moment, rendered with incredible realism and attention to detail. The center of the composition is occupied by the table upon which the woman lies, with her face expressing a mixture of fatigue, hope and pain. Around her are gathered medical workers, their faces focused and serious. The doctors work in a coordinated and accurate manner, their hands moving with precision and care. In the background of the painting, a priest can be seen holding his breath and praying in anticipation of the miracle of birth. The atmosphere in the room is filled with tension, but also with solemn anticipation. The most touching moment of the painting is depicted in the center: the doctor removes the newborn baby from the incision in the mother's abdomen. The painting's colours convey the emotional intensity of the scene: bright whites contrast with the vibrant, warm colours of skin and blood, highlighting the fragility of life and the grandeur of the moment of birth – a true hymn to human resilience, love and scientific progress that makes possible such a miracle as birth of a new life through a Caesarean section.

Figure 11. Painting depicting the first successful Caesarean section in Latin America in 1844. Enrique Grau. Collection of the International Museum of Surgical Science.

Рисунок 11. Картина, изображающая первое успешное кесарево сечение в Латинской Америке в 1844 г. Энрике Грау. Коллекция Международного музея хирургической науки.

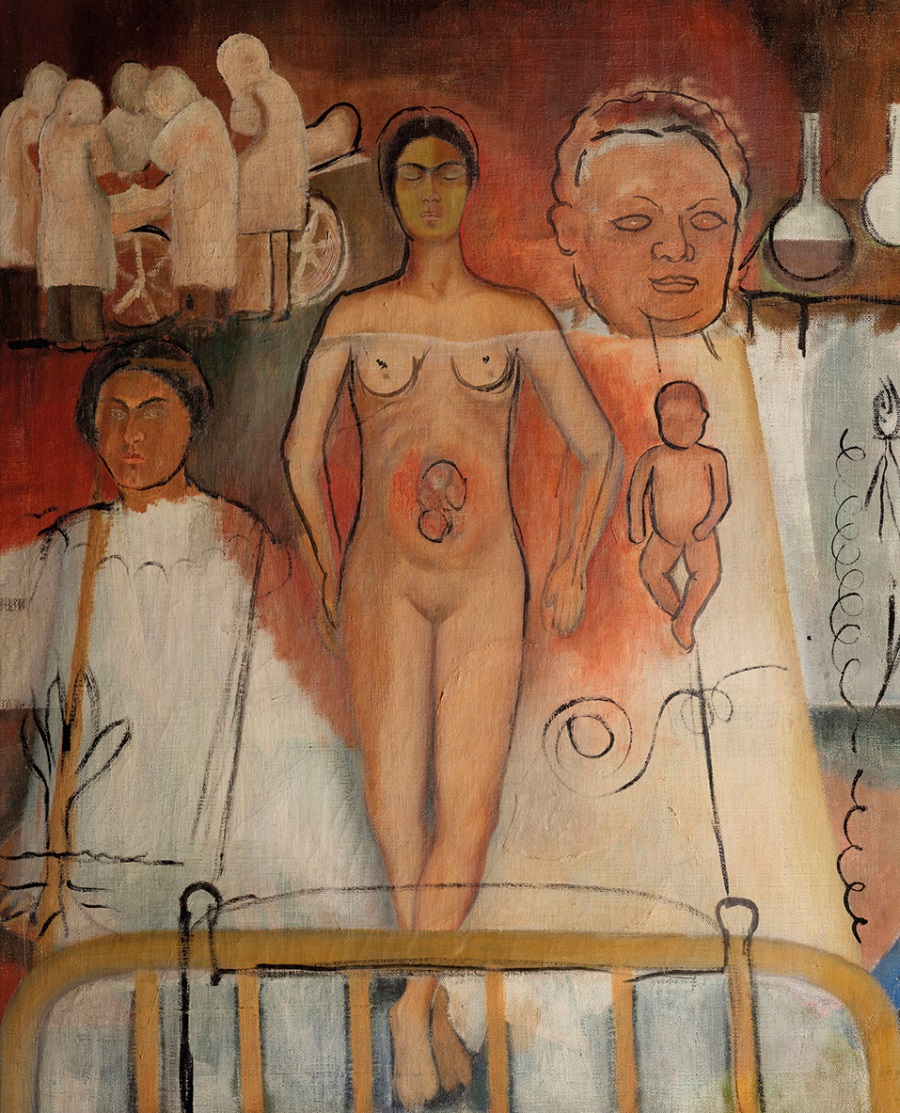

Moving into the 20th century, we find a clear reinforcement of the changed narrative. Frida Kahlo’s frank and bold work "Frida and the Caesarean Section" illustrates a woman’s newfound hope attempting to become a mother (Fig. 12). The artist’s personal history was filled with tragic experiences. For a long time, Frida struggled with the consequences of injuries sustained in an accident at a young age. Doctors predicted difficulties in carrying a pregnancy and giving birth. However, in case of a successful pregnancy, doctors provided a comforting alternative to natural resolution. For Frida, Caesarean section became a potential opportunity to have a child. The painting "Frida and the Caesarean Section" became a creative embodiment of this hope, intertwined with the experiences and fears of that period. The composition of the painting is a mixture of surrealism and magical realism.

Figure 12. Frida Kahlo. "Frida and the Caesarean Section", 1931.

Рисунок 12. Фрида Кало. «Фрида и кесарево сечение», 1931 г.

The main colors of the work can symbolize two worlds: dark brown and red – material, earthly, physical; light – the heavenly, spiritual, sublime world. The female figure of Frida is located as if between these two worlds, which can symbolically tell about struggle and attempt to find harmony between the limitations of body and spirit’s needs. The light image of doctors leaning over the operating table relates them to the world of higher, divine forces doing their work on earth. However, the archetypal attitudes we touched upon in the above-mentioned myth of the Asclepius’s birth are also revealed here. The purity of the light image may consist of duality and in some own part also denote sterility, fruitlessness referring to the fear in front of punishment and the ruthlessness of the gods. Shades of red enhance the ambivalence of perception, symbolizing the experience of pain and suffer. The impressions from viewing this work are far from stable unambiguity. Nevertheless, hope and possibility of a favorable perspective hold an essential place in here.

Continuing along the path of surrealism, the scope of our topic will not allow to pass by the work by Salvador Dali "Geopolitical Child Watching the Birth of a New Man" (Fig. 13). The range of meanings and interpretations that emerge while reviewing it strikes by its breadth. We will touch upon only a small part of it. The very image of the appearance of man through a cut on the planet’s body reflects the idea of the naturalness of modern man’s arrival into the world via a new handmade way. Not only natural processes provide an opportunity to be born and to be on Earth, but also new methods invented and controlled by man are becoming the norm. Mankind creates itself with its own hands, not appealing to the gods with the same fear. Caesarean section as a phenomenon is legitimized by the absence of past losses and, undoubtedly, along with other innovations, changes social reality.

Figure 13. Salvador Dali "Geopolitical Child Watching the Birth of a New Man", 1943.

Рисунок 13. Сальвадор Дали «Геополитический ребенок, наблюдающий за рождением нового человека», 1943 г.

The next work by Taisiya Korotkova, "Caesarean Section" dated of 2010, makes a viewer to witness the operation in its own realistic manner (Fig. 14). By all indications, we can understand that this is a Caesarean section, but the visual absence of mother in this event inevitably raises questions. According to the picture’s author, while studying such issues she is interested in an interplay between man and society and modern science, industry as well as emerging technologies. The artist comments on this: "Science per se is neutral, it is a tool, and how to use it depends on the person". Four female doctors bending over the baby look unperturbed, it seems that the movements they make are measured and honed by experience, their faces are calm. Such confidence in the process, the absence of suffer and uncertainty can definitely be considered an achievement that resulting from medicine’s desire and persistence. However, not a single adult’s glance is shed at a child in the painting thereby creating an image of a perfectly functioning system, in which feelings and emotional connection are far from being paramount. The themes that the author raises reveal paradoxes in the perception of long-awaited progress. Does the absence of pain during childbirth deprive the human nature, turning the process into production or, on the contrary, saves the human, by directly preserving people's lives? These questions remain for an observer to ponder.

Figure 14. Taisiya Korotkova. "Caesarean section", 2010.

From the “Reproduction” Series (2010–2012).

Рисунок 14. Таисия Короткова. «Кесарево сечение», 2010 г.

Из Серии «Репродукция» (2010–2012).

Conclusion / Заключение

Caesarean section is one of the ancient and most outstanding operations, with roots going deep into the past. Its unmatched significance is that it is the only operation responsible for the lives of two people – mother and child. Our interest is focused not so much on medical aspects, but rather in its visualization in art. Studying artistic works related to Caesarean section helps us to better understand its impact on mankind and social consciousness. Analyzing Сaesarean section this was allows to gain a deeper insight into the essence of such surgical practice and consider it in the context of cultural and social norms. Such an approach, which covers not only medical processes but also their impact on society, contributes to a deeper understanding of medicine per se and a role it plays in society.

References

1. Shakespeare W. Macbeth: a tragedy. Translated from English by B. Pasternak. [Makbet: tragediya. Per. s angl. B. Pasternaka]. Moscow: Martin, 2018. 142 p. (In Russ.).

2. Craufurd George. History of the Shire of Renfrew, 1710. 3345 р.

3. Ambroise Paré. Cinqlivres de chirurgie, 1579. 470 р.

4. Makatsariya N.A. Francois Maurice. [Fransua Moriso]. Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproduction. 2014;8(1):80–1. (In Russ.).

5. Mauriceau F. Traite des Maladies des Femmes Grosses et de Celles Qui Sont Accouchets. Paris, 1668. 515 р.

6. O’Dowd M.J., Philipp E.E. The history of Obstetrics and Gynecology. New York/London: The Parthenon publishing group, 1994. 651–2.

7. Makatsariya N.A. Father of British obstetrics. Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproduction. 2015;9(3):66–7. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17749/2070-4968.2015.9.3.066-067.

8. Baudelocque J.L. L’art des accouchemens. Paris: Méquignon, 1781. 486 р.

9. Makatsariya N.A. The Great Baudelocque. [Velikij Bodelok]. Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproduction. 2014;8(4):51–2. (In Russ.).

10. Porro E, Dell' amputazione utero-ovarica come complemento di taglio cesereo. Ann univ med e chir (Milan). 1876. 91 р.

11. Makatsariya N.A. Eduardo Porro. [Eduardo Porro]. Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproduction. 2014;8(3):76–8. (In Russ.).

About the Authors

N. V. MatveevaRussian Federation

Natalia V. Matveeva, MD

62 Str. Zemlyanoy Val, Moscow 109004

N. A. Makatsariya

Russian Federation

Nataliya A. Makatsariya, MD, PhD

8 bldg. 2, Trubetskaya Str., Moscow 119991

WoS ResearcherID: F-8406-2017

Review

For citations:

Matveeva N.V., Makatsariya N.A. Caesarean section through the prism of fine art and mythological stories. Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproduction. 2024;18(5):761–768. https://doi.org/10.17749/2313-7347/ob.gyn.rep.2024.558

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.