Scroll to:

An impact of neutrophil extracellular traps to the prothrombotic state and tumor progression in gynecological cancer patients

https://doi.org/10.17749/2313-7347/ob.gyn.rep.2023.385

Abstract

Introduction. One of the leading causes in the mortality pattern of cancer patients is accounted for by thrombotic complications. Recent studies have shown that neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) are involved in the activation of coagulation, contribute to the initiation and progression of thrombosis. In addition, NET-related effect on tumor progression and metastasis has been actively studied.

Aim: to evaluate NET-related procoagulant activity in gynecological cancer patients.

Materials and Methods. From April 2020 to October 2022, a prospective controlled interventional non-randomized study was conducted with 120 women. The main group included 87 patients aged 32 to 72 years with malignant neoplasms of the female genital organs and mammary glands who were hospitalized for elective surgical treatment or chemotherapy: uterine body cancer (subgroup 1; n = 18), ovarian cancer (subgroup 2; n = 26), cervical cancer – adenocarcinoma of the cervical canal (subgroup 3; n = 13), breast cancer (subgroup 4; n = 30). The control group consisted of 33 healthy women aged 32 to 68 years. In all women, plasma concentrations of citrullinated histone H3 (citH3), myeloperoxidase antigen (MPO:Ag), D-dimer, and thrombin–antithrombin (TAT) complexes were evaluated.

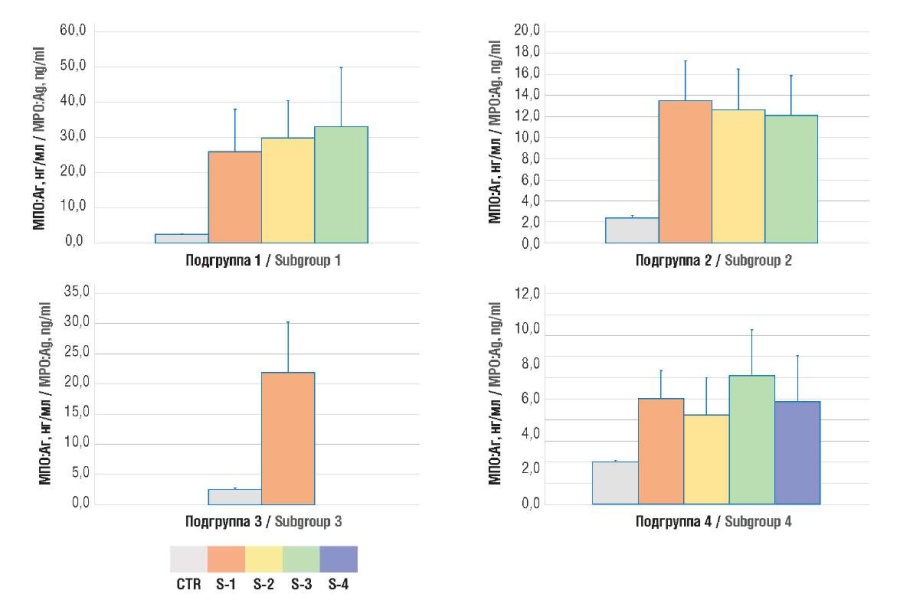

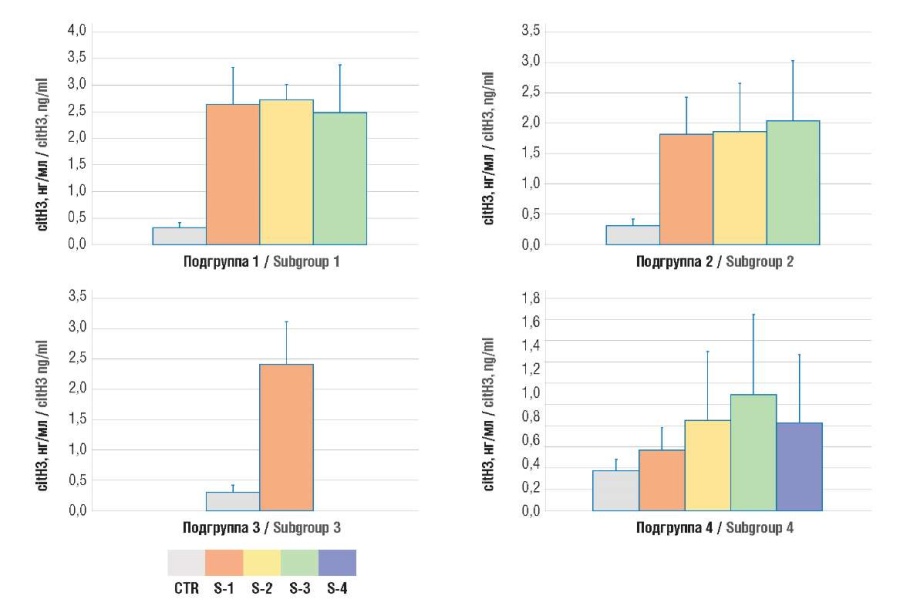

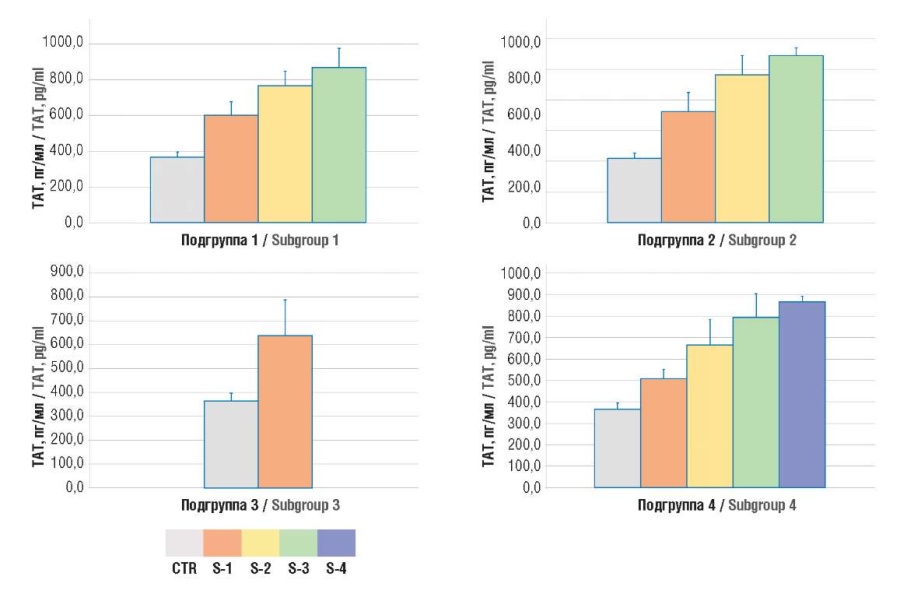

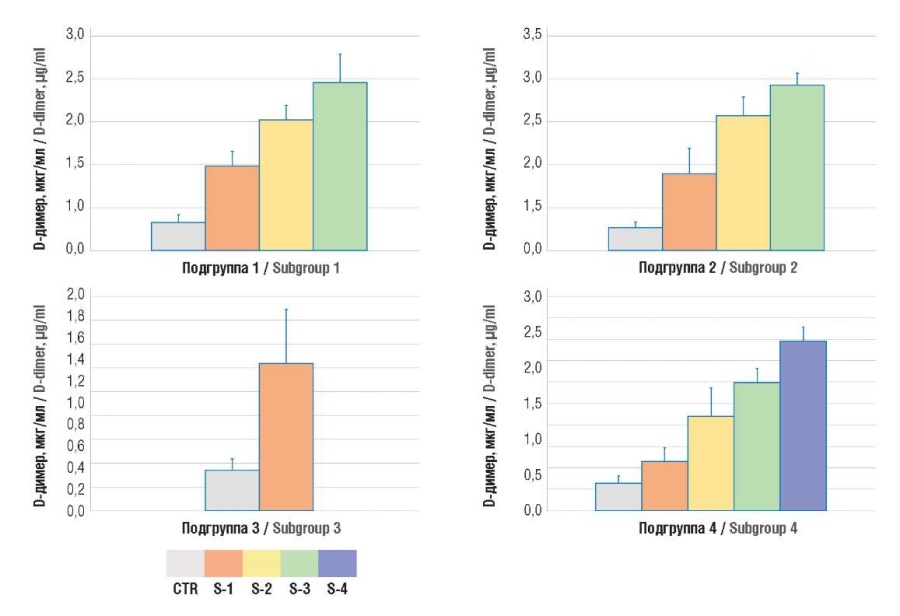

Results. The magnitude of NETosis in cancer patients, assessed by level of citH3 (2.5 ± 0.7; 1.9 ± 0.8; 2.5 ± 0.7; 0.7 ± 0.5 ng/ml in four subgroups, respectively) and MPO:Ag (29.5 ± 13.1; 12.8 ± 3.7; 22.8 ± 8.7; 6.6 ± 2.5 ng/ml in four subgroups, respectively) was significantly higher compared to women in the control group (0.3 ± 0.1 ng/ml; p = 0.0001 and 2.5 ± 0.2 ng/ml; p = 0.0001). In parallel with increased NETosis markers in accordance with the disease stage, there was an increase in the concentration of hemostasis activation markers – D-dimer (1.7 ± 0.6; 2.0 ± 0.7; 1.4 ± 0.5; 1.5 ± 0.7 µg/ml in four subgroups, respectively) and TAT complexes (729.8 ± 43.9; 794.1 ± 164.8; 636.2 ± 149.5; 699.6 ± 165.7 pg/ml in four subgroups, respectively) exceeding their level in the control group (respectively, 0.4 ± 0.1 μg/ml; p = 0.0001 and 362.3 ± 0.1 pg/ml; p = 0.0001). The maximum values of parameters occurred at later stages according to the Classification of Malignant Tumours (tumor, nodus, metastasis, TNM). A significant correlation between TAT level and the concentrations of citH3 (r = 0.586; р = 0.04) and MPO:Ag was revealed (r = 0.631; р = 0.04).

Conclusion. Tumor tissue creates milieu that stimulates NETs release, which, in turn, not only contribute to the creating a procoagulant state, but also might act as one of the factors that ensure tumor progression and metastasis. The development of targeted therapies acting on NETs has a potential to affect hemostasis in cancer patients and reduce rate of tumor growth and metastasis.

Keywords

For citations:

Slukhanchuk E.V., Bitsadze V.O., Solopova A.G., Khizroeva J.Kh., Degtyareva N.D., Shcherbakov D.V., Gris J., Elalamy I., Makatsariya A.D. An impact of neutrophil extracellular traps to the prothrombotic state and tumor progression in gynecological cancer patients. Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproduction. 2023;17(1):53-64. https://doi.org/10.17749/2313-7347/ob.gyn.rep.2023.385

Introduction / Введение

Hypercoagulation accompanies carcinogenesis, tumor progression, and metastasis. It is also associated with higher risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) as the second leading cause of death in cancer patients [1]. On the other hand, thromboprophylaxis and prophylactic anticoagulant therapy in cancer patients can reduce thrombosis risk improving survival [2]. However, anticoagulant therapy is associated with VTE occurrence and high risk of bleeding [3]. Thus, a deeper insight into understanding of hypercoagulation pathogenesis in cancer patients is necessary to develop new antithrombotic strategies.

Recent studies have shown that activated neutrophils produce neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), consisted of extracellular DNA, histones, cytoplasmic proteins, and neutrophil granule proteins. NETs are considered to be a part of a new procoagulant mechanism and a link between inflammation and thrombosis [4]. NETs extracellular DNA leads to coagulation activation [5], whereas histones induce platelet and erythrocyte activation. Inflammation always accompanies carcinogenesis [6]. One of the studies showed that neutrophils increased NETs production in mice with cancer and were directly involved in thrombogenesis [7]. In addition, NETs were shown to accompany cancer-associated organ failure [8]. Thus, we hypothesized that tumor growth stimulates neutrophils to release NETs in gynecological cancer patients resulting in activated coagulation and may be one of metastasis factors underlying metastasis that confirmed NET-related procoagulant activity in gynecological cancer patients.

Aim: to evaluate the NETs procoagulant activity in gynecological cancer patients.

Materials and Мethods / Материалы и методы

Study design / Дизайн исследования

Between April 2020 and October 2022, 120 women including 87 patients aged 34 to 72 years hospitalized for elective surgical treatment or chemotherapy at the University Clinical Hospital No 4 of Sechenov University and Petrovsky National Research Centre of Surgery (main group), and 33 medical staff members aged 32 to 68 years (control group) were enrolled in a prospective controlled interventional non-randomized study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria / Критерии включения и исключения

Inclusion criteria (main group): age over 18; diagnosis at admission – ovarian cancer, uterine cancer, cervical cancer and mammary cancer, confirmed by instrumental, laboratory and clinical examination; signed informed voluntary consent to participate in the study.

Inclusion criteria (control group): age over 18; no active cancer and oncological diseases, thrombosis and thromboembolism, chronic inflammatory diseases in history; signed informed consent to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria (for both groups): age under 18; active infectious and/or inflammation; cardiovascular diseases, severe course; decompensated diabetes mellitus; chronic diseases of the liver and kidneys in the acute stage; other concomitant oncological diseases; thromboembolic complications associated with coagulopathy and thrombocytopathy; anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents use; thrombotic or hemorrhagic syndrome at the time of examination; refusal to participate in the study.

Patients groups / Группы обследованных

The main group included breast and gynecologic cancer patients, stage I–III: uterine cancer (subgroup 1; n = 18, including 7 patients at stage 1TNM, 5 patients at stage 2TNM, 6 patients at stage 3TNM), ovarian cancer (subgroup 2; n = 26, 11 patients at stage 1TNM, 5 patients at stage 2TNM, 10 patients at stage 3TNM), cervical adenocarcinoma (subgroup 3; n = 13; all at stage 1TNM), breast cancer (subgroup 4; n = 30, 9 patients at stage 1TNM, 6 patients at stage 2TNM, 7 patients at stage 3TNM, 8 patients at stage 4TNM). The control group included 33 healthy women.

Study methods / Методы исследования

Plasma samples were obtained by venipuncture from all patients once upon admission (before surgical treatment, anticoagulants therapy, chemotherapy), centrifuged and stored at –80° C. Fasting blood samples were collected from the cubital vein into a plastic tube added with anticoagulant (sodium citrate solution 3.8 %) in a ratio of 9:1 using a dry sterile needle.

Assessing NETosis markers / Определение маркеров нетоза

To determine the human myeloperoxidase antigen (MPO:Ag) concentration in the blood plasma, a Hycult Biotech ELISA kit (Netherlands) was used, normal MPO:Ag reference level was 2.56 ± 0.33 ng/ml.

The citrullinated histone H3 (citH3) in blood plasma was measured using the Citrullinated Histone H3 ELISA Kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, USA).

Assessing markers of thrombinemia and fibrin formation / Определение маркеров тромбинемии и фибринообразования

Thrombinemia markers – thrombin-antithrombin complexes (TAT) were determined by enzyme-linked immunoassay, using the Siemens Healthineers EnzygnostTM TAT MicroKit (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Products GmbH, Germany) on a Boehnringer ELISA-Photometer spectrophotometer (Boehnringer, Germany).

D-dimer was measured using a commercial immunoassay (TECHNOLEIA®, Austria, Techoclone reagent). According to the manufacturer's data, D-dimer concentration > 250 ng/mL was considered pathological.

Ethical aspects / Этические аспекты

Informed consent was obtained from all patients to participate in the study and to process personal data in accordance with the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki (WMA Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects, 2013).

Statistical analysis / Статистический анализ

Data processing was performed using a specialized software Statistica 7.0 (StatSoft, Inc., USA).

Statistical analysis included descriptive statistics: arithmetic mean (M), standard deviation (SD), minimum and maximum values of laboratory parameters.

The normality test was performed using the Jarque-Bera test. The null hypothesis H0 that residual values of participant groups parameters have a normal distribution was rejectedat the significance level p ≤ 0.05.

Non-parametric test and inter-group parameter magnitude comparison was performed using the Mann-Whitney test for unrelated samples (Mann–Whitney U-test). The null hypothesis H0 was proposed as the absence of differences between patient groups. H0 was deviated in all cases at significance level of p ≤ 0.05.

When studying the relationships between variables in terms of reflecting the corresponding causal relationships between the MPO:Ag and citH3 values, we calculated the ρ-coefficient of Spearman Rank Order Correlations with fixing the coefficient significance level in the correlation matrix at the significance level p ≤ 0.05.

Results / Результаты

Сlinical and anamnestic characteristic / Клинико-анамнестическая характеристика обследованных пациенток

The clinical and anamnestic characteristics of individuals examined are presented in Table 1.

NETosis intensity in oncogynecological patients / Интенсивность нетоза у онкогинекологических пациенток

The NETosis intensity in oncogynecological patients was assessed based on the following markers (MPO:Ag and citH3) level. It was shown that both markers were significantly elevated in cancer patients than in healthy individuals (Table 1, Fig. 1, 2).

Table 1. Clinical and anamnestic characteristics.

Таблица 1. Клинико-анамнестическая характеристика.

|

Parameter Показатель |

Cancer patients (main group) Онкологические пациентки (основная группа) n = 87 |

Control group Контрольная группа n = 33 |

|||

|

Uterine cancer (subgroup 1) Рак тела матки (подгруппа 1) n = 18 |

Ovarian cancer (subgroup 2) Рак яичников (подгруппа 2) n = 26 |

Cervical cancer (subgroup 3) Рак шейки матки (подгруппа 3) n = 13 |

Brest cancer (subgroup 4) Рак молочной железы (подгруппа 4) n = 30 |

||

|

Age, years, М ± SD Возраст, лет, М ± SD Min–max |

52,2 ± 7,8* 40 – 67 |

55,7 ± 8,1* 42–68 |

48,2 ± 12,1 34–72 |

46,6 ± 6,0 36–61 |

45,4 ± 10,9 30–68 |

|

TAT concentration, pg/ml, М ± SD Концентрация ТАТ, пг/мл, M ± SD Min–max |

729,8 ± 43,9* 486–987 |

794,1 ± 164,3* 467–1002 |

636,2 ± 149,5* 478–907 |

699,6 ± 165,7* 465–974 |

362,3 ± 0,2 323–440 |

|

D-dimer concentration, µg/ml, М ± SD Концентрация D-димера, мкг/мл, M ± SD Min–max |

1,7 ± 0,6* 0,9–2,9 |

2,0 ± 0,7* 0,6–3,0 |

1,4 ± 0,5* 0,7–2,5 |

1,5 ± 0,7* 0,4–2,7 |

0,4 ± 0,1 0,2–0,6 |

|

citH3 concentration, ng/ml, М ± SD Концентрация сitH3, нг/мл, M ± SD Min–max |

2,6 ± 0,7* 1,1–3,5 |

1,9 ± 0,8* 1,0–3,5 |

2,5 ± 0,7* 0,9–3,2 |

0,7 ± 0,5* 0,1–2,1 |

0,3 ± 0,1 0,1–0,6 |

|

MPO: Ag concentration, ng/ml, М ± SD Концентрация MПО:Аг, нг/мл, M ± SD Min–max |

29,5 ± 13,1* 12,0–51,0 |

12,8 ± 3,7* 9,1–21,5 |

22,8 ± 8,7* 8,1–31,0 |

6,6 ± 2,5* 3,4–12,9 |

2,5 ± 0,2 2,2–2,8 |

|

TNM stage Стадия TNM |

1TNM (n = 7) 2TNM (n = 5) 3TNM (n = 6) |

1TNM (n = 11) 2TNM (n = 5) 3TNM (n = 10) |

1TNM (n = 13) |

1TNM (n = 9) 2TNM (n = 6) 3TNM (n = 7) 4TNM (n = 8) |

нет |

Note: *p < 0.05 – significant differences compared to the control group; TAT – thrombin–antithrombin complexes; citH3 – citrullinated histone H3; MPO:Ag – human myeloperoxidase antigen; TNM (tumor, nodus, metastasis) – staging.

Примечание: *р < 0,05 – различия статистически значимы по сравнению с контрольной группой; ТАТ – комплексы тромбин–антитромбин; сitH3 – цитруллинированный гистон Н3, МПО:Аг – антиген миелопероксидазы человека; TNM – стадирование.

Figure 1. Plasma level of human myeloperoxidase antigen (MPO:Ag).

Note: subgroup 1 – uterine body cancer; subgroup 2 – ovarian cancer; subgroup 3 – cervical cancer; subgroup 4 – breast cancer; CTR – control group; S1-4 – TNM stages 1-4.

Рисунок 1. Содержание антигена миелопероксидазы человека (MПO:Aг) в плазме крови.

Примечание: подгруппа 1 – рак тела матки; подгруппа 2 – рак яичников; подгруппа 3 – рак шейки матки; подгруппа 4 – рак молочной железы; CTR – контрольная группа; S1-4 – стадии TNM 1-4.

Figure 2. Plasma level of citrullinated histone H3 (citH3).

Note: subgroup 1 – uterine body cancer; subgroup 2 – ovarian cancer; subgroup 3 – cervical cancer; subgroup 4 – breast cancer; CTR – control group; S1-4 – TNM stages 1-4.

Рисунок 2. Содержание цитруллинированного гистона H3 (citH3) в плазме крови.

Примечание: подгруппа 1 – рак тела матки; подгруппа 2 – рак яичников; подгруппа 3 – рак шейки матки; подгруппа 4 – рак молочной железы; CTR – контрольная группа; S1-4 – стадии TNM 1-4.

Hemostasis activation in oncogynecological patients / Активация гемостаза у онкогинекологических пациенток

While analyzing the D-dimer and TAT levels in oncogynecological patients, they were found to be significantly increased compared with control group, which continued to rise along with aggravated TNM stage (Fig. 3, 4).

Subsequent correlation analysis revealed a significant correlation between the increased levels of TAT complexes as well as citH3 and MPO:Ag (Tables 2, 3).

Figure 3. Plasma level of thrombin–antithrombin (TAT) complexes.

Note: subgroup 1 – uterine body cancer; subgroup 2 – ovarian cancer; subgroup 3 – cervical cancer; subgroup 4 – breast cancer; CTR – control group; S1-4 – TNM stages 1-4.

Рисунок 3. Содержание комплексов тромбин–антитромбин (ТАТ) в плазме крови.

Примечание: подгруппа 1 – рак тела матки; подгруппа 2 – рак яичников; подгруппа 3 – рак шейки матки; подгруппа 4 – рак молочной железы; CTR – контрольная группа; S1-4 – стадии TNM 1-4.

Figure 4. Plasma D-dimer level.

Note: subgroup 1 – uterine body cancer; subgroup 2 – ovarian cancer; subgroup 3 – cervical cancer; subgroup 4 – breast cancer; CTR – control group; S1-4 – TNM stages 1-4.

Рисунок 4. Содержание D-димера в плазме крови.

Примечание: подгруппа 1 – рак тела матки; подгруппа 2 – рак яичников; подгруппа 3 – рак шейки матки; подгруппа 4 – рак молочной железы; CTR – контрольная группа; S1-4 – стадии TNM 1-4.

Table 2. Correlations between NETosis markers (citH3 and MPO:Ag), thrombin–antithrombin complex (TAT) and D-dimer levels.

Таблица 2. Корреляции между содержанием маркеров нетоза (citH3 и МПО:Аг) и комплексов тромбин–антитромбин (ТАТ) и D-димера.

|

Parameter Показатель |

TAT level, pg/ml Концентрация ТАТ, пг/мл |

D-dimer level, ng/ml Концентрация D-димерa, нг/мл |

||

|

r |

p |

r |

p |

|

|

citH3 level, ng/ml Концентрация citH3, нг/мл |

0,585644 |

р = 0,04 |

0,415624 |

p > 0,05 |

|

MPO:Ag level, ng/ml Концентрация МПО:Аг, нг/мл |

0,630720 |

р = 0,04 |

0,472069 |

p > 0,05 |

Table 3. A correlation matrix between the concentrations of NETosis markers (citH3 and MPO:Ag), thrombin–antithrombin complexes (TAT) and D-dimer (according to Spearman).

Таблица 3. Корреляционная матрица между концентрациями маркеров нетоза (citH3 и МПО:Аг) и комплексов тромбин–антитромбин (ТАТ) и D-димера (по Спирмену).

|

Spearman's rank correlation coefficient / Коэффициент ранговой корреляции Спирмена p < 0,04000 |

||||

|

Parameter Показатель |

TAT, pg/ml ТАТ, пг/мл |

D-dimer, ng/ml D-димер, нг/мл |

citH3, ng/ml citН3, нг/мл |

MPO:Ag, ng/ml MПO:Aг, нг/мл |

|

TAT, pg/ml ТАТ, пг/мл |

1,00 |

0,90 |

0,59 |

0,63 |

|

D-dimer, ng/ml D-димер, нг/мл |

0,90 |

1,00 |

0,42 |

0,47 |

|

citH3, ng/ml citН3, нг/мл |

0,59 |

0,42 |

1,00 |

0,82 |

|

MPO:Ag, ng/ml MПO:Aг, нг/мл |

0,63 |

0,47 |

0,82 |

1,00 |

Discussion / Обсуждение

Hypercoagulation profoundly elevates mortality rate in cancer patients [9]. Armand Trousseau firstly described the relationship between idiopathic VTE and latent tumors highlighting the correlation between cancer and thrombosis. Recent studies have shown that NETs are involved in activating coagulation, promoting initiation and thrombosis progression. In addition, NETs contribution to tumor progression and metastasis is being actively studied

NETs were first described in 2004 [10]. NETs are produced by activated neutrophils during NETosis originally recognized as a host defense mechanism. NETs are derivatives of activated neutrophils consisting of DNA strands and histones that grab and hold various pathogens until they are destroyed by NET-associated enzymes [11].

However, NETosis began to be determined in aseptic inflammation [4][12][13]. The role of NETs in autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis has been demonstrated [14–16]. NETs are also involved in the pathogenesis of thrombosis in diabetes mellitus, atherosclerosis, and vasculitis [17–19].

NETs affect the hemostasis system in various ways, contributing to the procoagulant state and disrupting the anticoagulants functioning and fibrinolysis [20]. Neutrophils in mouse breast cancer and chronic myeloma leukemia stimulate increased NETs production with subsequent hemostasis activation [21].

The numerous NETs-related effects are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Procoagulant and antifibrinolytic effects of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs).

Таблица 4. Прокоагулянтные и антифибринолитические эффекты внеклеточных ловушек нейтрофилов (NETs).

|

NETs constituents Структуры NETs |

Effects on hemostasis arms Влияние на звенья гемостаза |

|

NETs DNA ДНК NETs |

NETs DNA triggers a coagulation cascade in intrinsic pathway, which, under pathological conditions with a massive DNA release due to cell damage and death, comes to the front line in the pathogenesis of thrombosis [22]. Negatively charged surfaces increase the activation of the factor (F) XII (FXII) initiator of this pathway [23] ДНК NETs запускает коагуляционный каскад по внутреннему пути, который при патологических состояниях с массивным выбросом ДНК в результате повреждения и гибели клеток выходит на передний план в патогенезе тромбоза [22]. Отрицательно заряженные поверхности повышают активацию инициатора этого пути фактора (F) XII (FXII) [23] |

|

NETs DNA acts as a cofactor for thrombin-dependent activation of factor XI [24] and contributes to successful progression of reactions of the extrinsic pathway associated with tissue factor [25] ДНК NETs выступает в качестве кофактора для тромбин-зависимой активации фактора XI [24] и способствует успешному протеканию реакций внешнего пути, связанного с тканевым фактором [25] |

|

|

NETs DNA enhances the formation of complexes between tissue plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) [26] ДНК NETs повышает формирование комплексов тканевого активатора плазминогена c ингибитором активатора плазминогена-1 (англ. inhibitor of plasminogen activator-1, PAI-1) [26] |

|

|

NETs DNA reduces the intensity of plasmin synthesis from plasminogen acted upon by tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) on the thrombus surface [27] ДНК NETs снижает интенсивность синтеза плазмина из плазминогена под действием активатора плазминогена тканевого типа (англ. tissue plasminogen activator, tPA) на поверхности тромба [27] |

|

|

NETs DNA binds proteins responsible for fibrin degradation and reduces their release by fibrin clots [28], as well as also penetrates fibrin strands and blocks plasmin-mediated clot lysis ДНК NETs связывает белки, ответственные за деградацию фибрина и уменьшает их выделение фибриновыми тромбами [28], а также проникает в нити фибрина и блокирует плазмин-опосредованный лизис тромба |

|

|

NETs histones Гистоны NETs |

NETs histones destroy endothelium anticoagulant barrier by forming holes in phospholipid membranes with impaired ion exchange [29][30]. In the process of endothelial activation and death [31], Н2О2 is released, further stimulating NETosis [32]. Weibel–Palade bodies located in the endothelium undergo exocytosis together with von Willebrand factor (vWF) Гистоны NETs разрушают антикоагулянтный барьер эндотелия путем формирования отверстий в фосфолипидных мембранах с нарушением ионообмена [29][30]. В процессе активации эндотелия и его гибели [31] происходит выделение Н2О2, далее стимулирующей нетоз [32]. Находящиеся в эндотелии тельца Вейбеля–Паладе подвергаются экзоцитозу совместно с фактором фон Виллебранда (англ. von Willebrand factor, vWF) |

|

NETs histones promote platelet activation [21][29] Гистоны NETs способствуют активации тромбоцитов [21][29] |

|

|

NETs histones affect proteins of the coagulation cascade [33] Гистоны NETs влияют на белки коагуляционного каскада [33] |

|

|

Histone H4 binds to prothrombin and promotes its autoactivation [33] Гистон Н4 связывается с протромбином и способствует его аутоактивации [33] |

|

|

Histones impair antithrombin-dependent thrombin inactivation [27], prevent thrombin–thrombomodulin interaction [34], trigger pathways for inactivation of activated protein C Гистоны нарушают антитромбин-зависимую инактивацию тромбина [27], препятствуют взаимодействию тромбин–тромбомодулин [34], запускают пути инактивации активированного протеина С |

|

|

Histones by activating soluble plasminogen, suppress plasmin acting as competitive substrates [35] Гистоны, активируя плазминоген в растворе, подавляют плазмин, выступая как конкурентные субстраты [35] |

|

|

Histones protect fibrin from the plasminogen action by covalently binding to fibrin, catalyzed by activated transglutaminase, clotting factor XIIIa. Through non-covalent interactions, histones promote lateral aggregation of fibrin protofibrils, resulting in thickening of its filaments and increased the mass–length ratio in them followed by hypofibrinolysis [35] Гистоны защищают фибрин от действия плазминогена путем ковалентного связывания с фибрином, катализируемого активированной трансглутаминазой, фактором свертывания XIIIа. Путем нековалентных взаимодействий гистоны способствуют латеральной агрегации протофибрил фибрина, приводя к утолщению его нитей и увеличению соотношения масса–длина в них, что приводит к гипофибринолизу [35] |

In the current study, NETs-dependent role was demonstrated in the gynecological patients with uterine, cervical, ovarian and breast cancer resulting in activated coagulation system. There were assessed the concentrations of NETosis markers, such as MPO:Ag and citH3 in gynecological cancer patients with different tumors at different stages. Simultaneously, there were investigated D-dimer and TAT complexes levels. In our study, an increased NETs production was noted as a significantly increased MPO:Ag and citH3 levels in cancer patients, mostly at late TNM stages. These data provide indirect evidence that rise in the tumor load causes increased NETs production.

In parallel with elevated NETosis markers, depending on the disease stage, there was also observed increased hemostasis activation markers (D-dimer and TAT complexes). A significant correlation was found between the TAT and thecit H3 as well as MPO:Ag levels.

In recent years, the NETs-related role in tumor growth has been actively studied. It has been proven that cells participating in the inflammatory response and inflammatory mediators contribute to cancer induction, tumor growth, and metastasis [36]. Some NETs components exert a cytotoxic effect, e.g., MPO damages melanoma cells. Patients with MPO deficiency have a higher risk of tumor progression and recurrence [37]. NETs histones corrode the tumor vasculature, destroy epithelial cells, and promote tumor cell lysis [7][38].

At the same time, NETs proteases can destroy the extracellular matrix, triggering metastasis. NETs-released matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) blocks tumor cell apoptosis and ensures migration, invasion, and metastasis, e.g., in lung cancer [39–41]. Moreover, NETs in patients with Ewing's sarcoma were shown to bear neutrophils actively releasing NETs in the tumor tissue. However, neutrophils and NETs were determined mainly in patients at late stages with metastases. The disease relapsed rapidly in patients with complete remission after chemotherapy [42].

Attaching to tumor cells, NETs facilitate the metastasis by binding the tumor cell and endothelium in the target organ of metastasis. In animal models it has been shown that after NETs fixation to the vascular endothelium, they begin to grab tumor cells via DNA strands from the bloodstream. Thus, the NETs production, tumor progression, and metastasis can create a vicious circle in cancer patients. The aforementioned mechanism allows to consider NETs as one of the players in the metastasis, and hence as a potential therapeutic target. It is potentially plausible to prevent the NETs-related effect on tumor progression by administering elastase or DNase inhibitors [43].

In our study along with assessing NETosis marker levels, there were analyzed hemostasis activation markers (TAT and D-dimer) so that all patients were found to have significantly activated hemostasis. However, while conducting a correlation analysis, a significant correlation was observed only between TAT complex and NETosis marker levels.

Animal cancer models were featured with increased tissue neutrophil infiltration in various organs paralleled with vascular damage and platelet-neutrophil complexes due to massive necrosis. Administering DNase had a positive effect in regression of such conditions again confirming the NETosis-related contribution to developing multiple organ failure in cancer patients [8]. Recent studies on animals have shown that the NETosis suppression lowers a rise in the prothrombotic state and metastasis [7][8][43].

Thus, NETs play one of the major roles in triggering blood clotting in cancer patients. Accordingly, NETs can act as a target for novel approaches to develop thromboprophylaxis [44]. Assessing NETosis markers represents a potential screening approach for initial hemostasis di- sorders when the first-line laboratory tests have not been changed yet.

Conclusion / Заключение

The study results indicate that the tumor tissue creates conditions stimulating neutrophils to release procoagulant extracellular traps, which, in turn, not only contribute to creating procoagulant state, but also ensure metastasis. Developing therapies targeting NETs may potentially affect hemostasis system in cancer patients and reduce magnitude of metastasis spread.

References

1. Timp J.F., Braekkan S.K., Versteeg H.H., Cannegieter S.C. Epidemiology of cancer-associated venous thrombosis. Blood. 2013;122(10):1712–23. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-04-460121.

2. Klerk C.P., Smorenburg S.M., Otten H.-M. et al. The effect of low molecular weight heparin on survival in patients with advanced malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(10):2130–5. https://doi.org/10.1200/ JCO.2005.03.134.

3. Akl E.A., Schünemann H.J. Routine heparin for patients with cancer? One answer, more questions. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(7):661–2. https://doi. org/10.1056/NEJMe1113672.

4. Stakos D.A., Kambas K., Konstantinidis T. et al. Expression of functional tissue factor by neutrophil extracellular traps in culprit artery of acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(22):1405–14. https://doi. org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv007.

5. Gould T.J., Vu T.T., Swystun L.L. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps promote thrombin generation through platelet-dependent and plateletindependent mechanisms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34(9):1977–84. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304114.

6. Hanahan D., Weinberg R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013.

7. Demers M., Krause D.S., Schatzberg D. et al. Cancers predispose neutrophils to release extracellular DNA traps that contribute to cancerassociated thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(32):13076– 81. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1200419109.

8. Cedervall J., Zhang Y., Huang H. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps accumulate in peripheral blood vessels and compromise organ function in tumor-bearing animals. Cancer Res. 2015;75(13):2653–62. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3299.

9. Nierodzik M.L., Karpatkin S. Thrombin induces tumor growth, metastasis, and angiogenesis: Evidence for a thrombin-regulated dormant tumor phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2006;10(5):355–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.002.

10. Brinkmann V., Reichard U., Goosmann C. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303(5663):1532–5. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1092385.

11. Papayannopoulos V. Neutrophil extracellular traps in immunity and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18(2):134–47. https://doi.org/10.1038/ nri.2017.105.

12. Wong S.L., Demers M., Martinod K. et al. Diabetes primes neutrophils to undergo NETosis, which impairs wound healing. Nat Med. 2015;21(7):815–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3887.

13. Schauer C., Janko C., Munoz L.E. et al. Aggregated neutrophil extracellular traps limit inflammation by degrading cytokines and chemokines. Nat Med. 2014;20(5):511–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3547.

14. El-Shebini E.M., Shoeib S.A., Elghotmy A.H. Neutrophil extracellular traps in systemic lupus erythematosus. Menoufia Med J. 2020;33(3):729–32. https://doi.org/10.4103/mmj.mmj_431_18.

15. Manneras-Holm L., Baghaei F., Holm G. et al. Coagulation and fibrinolytic disturbances in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(4):1068–76. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2010-2279.

16. Gray R.D., Hardisty G., Regan K.H. et al. Delayed neutrophil apoptosis enhances NET formation in cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2018;73(2):134–44. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210134.

17. Fuchs T.A., Brill A., Duerschmied D. et al. Extracellular DNA traps promote thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(36):15880–5. https://doi. org/10.1073/pnas.1005743107.

18. Wang L., Zhou X., Yin Y. et al. Hyperglycemia induces neutrophil extracellular traps formation through an NADPH oxidase-dependent pathway in diabetic retinopathy. Front Immunol. 2019;9:3076. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.03076.

19. Warnatsch A., Ioannou M., Wang Q., Papayannopoulos V. Inflammation. Neutrophil extracellular traps license macrophages for cytokine production in atherosclerosis. Science. 2015;349(6245):316–20. https:// doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa8064.

20. Gould T., Lysov Z., Liaw P. Extracellular DNA and histones: double-edged swords in immunothrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13 Suppl 1:S82– S91. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.12977.

21. Demers M., Wagner D.D. Neutrophil extracellular traps: A new link to cancer-associated thrombosis and potential implications for tumor progression. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2(2):e22946. https://doi.org/10.4161/onci.22946.

22. Delabranche X., Helms J., Meziani F. Immunohaemostasis: a new view on haemostasis during sepsis. Ann Intensive Care. 2017;7():117. https://doi. org/10.1186/s13613-017-0339-5.

23. Naudin C., Burillo E., Blankenberg S. et al. Factor XII contact activation. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2017;43(8):814–26. https://doi. org/10.1055/s-0036-1598003.

24. Vu T.T., Leslie B.A., Stafford A.R. et al. Histidine-rich glycoprotein binds DNA and RNA and attenuates their capacity to activate the intrinsic coagulation pathway. Thromb Haemost. 2016;115(1):89–98. https://doi.org/10.1160/TH15-04-0336.

25. Noubouossie D.F., Whelihan M.F., Yu Y.-B. et al. In vitro activation of coagulation by human neutrophil DNA and histone proteins but not neutrophil extracellular traps. Blood. 2017;129(8):1021–9. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2016-06-722298.

26. Komissarov A.A., Florova G., Idell S. Effects of extracellular DNA on plasminogen activation and fibrinolysis. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(49):41949–62. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M111.301218.

27. Varjú I., Longstaff C., Szabó L. et al. DNA, histones and neutrophil extracellular traps exert anti-fibrinolytic effects in a plasma environment. Thromb Haemost. 2015;113(6):1289–98. https://doi.org/10.1160/TH14-08-0669.

28. Longstaff C., Varjú I., Sótonyi P. et al. Mechanical stability and fibrinolytic resistance of clots containing fibrin, DNA, and histones. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(10):6946–56. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.404301.

29. Qi H., Yang S., Zhang L. Neutrophil extracellular traps and endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis and thrombosis. Front Immunol. 2017;8:928. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.00928.

30. Xu J., Zhang X., Pelayo R. et al. Extracellular histones are major mediators of death in sepsis. Nat Med. 2009;15(11):1318–21. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.2053.

31. Saffarzadeh M., Juenemann C., Queisser M.A. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps directly induce epithelial and endothelial cell death: a predominant role of histones. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e32366. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0032366.

32. Fuchs T.A., Abed U., Goosmann C. et al. Novel cell death program leads to neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol. 2007;176(2):231–41. https://doi. org/10.1083/jcb.200606027.

33. Barranco-Medina S., Pozzi N., Vogt A.D., Di Cera E. Histone H4 promotes prothrombin autoactivation. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(50):35749–57. https:// doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M113.509786.

34. Ammollo C.T., Semeraro F., Xu J. et al. Extracellular histones increase plasma thrombin generation by impairing thrombomodulin-dependent protein C activation. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(9):1795–803. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04422.x.

35. Gould T.J., Vu T.T., Stafford A.R. et al. Cell-free DNA modulates clot structure and impairs fibrinolysis in sepsis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35(12):2544–53. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306035.

36. Mantovani A., Allavena P., Sica A., Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454(7203):436–44. https://doi.org/10.1038/ nature07205.

37. Metzler K.D., Fuchs T.A., Nauseef W.M. et al. Myeloperoxidase is required for neutrophil extracellular trap formation: implications for innate immunity. Blood. 2011;117(3):953–9. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood2010-06-290171.

38. Al-Benna S., Shai Y., Jacobsen F., Steinstraesser L. Oncolytic activities of host defense peptides. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12(11):8027–51. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms12118027.

39. Acuff H.B., Carter K.J., Fingleton B. et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 from bone marrow–derived cells contributes to survival but not growth of tumor cells in the lung microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2006;66(1):259– 66. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2502.

40. Masson V., De La Ballina L.R., Munaut C. et al. Contribution of host MMP-2 and MMP-9 to promote tumor vascularization and invasion of malignant keratinocytes. FASEB J. 2005;19(2):234–6. https://doi. org/10.1096/fj.04-2140fje.

41. Pahler J.C., Tazzyman S., Erez N. et al. Plasticity in tumor-promoting inflammation: impairment of macrophage recruitment evokes a compensatory neutrophil response. Neoplasia. 2008;10(4):329–40. https://doi.org/10.1593/neo.07871.

42. Berger-Achituv S., Brinkmann V., Abu-Abed U. et al. A proposed role for neutrophil extracellular traps in cancer immunoediting. Front Iimmunol. 2013;4:48. https://doi.org/10.3389/ fimmu.2013.00048.

43. Cools-Lartigue J., Spicer J., McDonald B. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps sequester circulating tumor cells and promote metastasis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(8):3446–58. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI67484.

44. Gregory A.D., Houghton A.M. Tumor-associated neutrophils: new targets for cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2011;71()7:2411–6. https://doi. org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2583.

About the Authors

E. V. SlukhanchukRussian Federation

Ekaterina V. Slukhanchuk – MD, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatal Medicine, Filatov Clinical Institute of Children’s Health

2 bldg. 4, Bolshaya Pirogovskaya Str., Moscow 119991

V. O. Bitsadze

Russian Federation

Victoria O. Bitsadze – MD, Dr Sci Med, Professor of RAS, Professor, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatal Medicine, Filatov Clinical Institute of Children’s Health

2 bldg. 4, Bolshaya Pirogovskaya Str., Moscow 119991

A. G. Solopova

Russian Federation

Antonina G. Solopova – MD, Dr Sci Med, Professor, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatal Medicine, Filatov Clinical Institute of Children's Health

2 bldg. 4, Bolshaya Pirogovskaya Str., Moscow 119991

J. Kh. Khizroeva

Russian Federation

Jamilya Kh. Khizroeva – MD, Dr Sci Med, Professor, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatal Medicine, Filatov Clinical Institute of Children’s Health

Scopus Author ID: 57194547147

Researcher ID: F-8384-2017

2 bldg. 4, Bolshaya Pirogovskaya Str., Moscow 119991

N. D. Degtyareva

Russian Federation

Natalia D. Degtyareva – 5th year Student, Filatov Clinical Institute of Children’s Health

2 bldg. 4, Bolshaya Pirogovskaya Str., Moscow 119991

D. V. Shcherbakov

Russian Federation

Denis V. Shcherbakov – MD, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of General Hygiene, Erisman Institute of Public Health

2 bldg. 4, Bolshaya Pirogovskaya Str., Moscow 119991

J.-C. Gris

Russian Federation

Jean-Christophe Gris – MD, Dr Sci Med, Professor, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatal Medicine, Filatov Clinical Institute of Children’s Health; Professor of Haematology, Head of the Laboratory of Haematology, Faculty of Biological and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Montpellier University and University Hospital of Nîmes; Foreign Member of RAS

Scopus Author ID: 7005114260

Researcher ID: AAA-2923-2019

2 bldg. 4, Bolshaya Pirogovskaya Str., Moscow 119991

163 Rue Auguste Broussonnet, Montpellier 34090

I. Elalamy

Russian Federation

Ismail Elalamy – MD, Dr Sci Med, Professor, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatal Medicine, Filatov Clinical Institute of Children’s Health; Director of Hematology, Department of Thrombosis Center, Hospital Tenon

Scopus Author ID: 7003652413

Researcher ID: AAC-9695-2019

2 bldg. 4, Bolshaya Pirogovskaya Str., Moscow 119991

12 Rue de l’École de Médecine, Paris 75006, France

4 Rue de la Chine, Paris 75020, France

A. D. Makatsariya

Russian Federation

Alexander D. Makatsariya – MD, Dr Sci Med, Academician of RAS, Professor, Head of the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatal Medicine, Filatov Clinical Institute of Children’s Health

Scopus Author ID: 57222220144

Researcher ID: M-5660-2016

2 bldg. 4, Bolshaya Pirogovskaya Str., Moscow 119991

Review

For citations:

Slukhanchuk E.V., Bitsadze V.O., Solopova A.G., Khizroeva J.Kh., Degtyareva N.D., Shcherbakov D.V., Gris J., Elalamy I., Makatsariya A.D. An impact of neutrophil extracellular traps to the prothrombotic state and tumor progression in gynecological cancer patients. Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproduction. 2023;17(1):53-64. https://doi.org/10.17749/2313-7347/ob.gyn.rep.2023.385

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.