Scroll to:

An exposition on complete androgen insensitivity syndrome and a case report

https://doi.org/10.17749/2313-7347/ob.gyn.rep.2025.539

Abstract

Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS) is a rare X-linked sexual development condition typified by 46,XY karyotype, presence of external female genitalia along with intra-abdominal testes in labia majora or inguinal ring region. This syndrome results from alterations in the androgen receptor (AR) gene leading to primary amenorrhea and uterine agenesis (Müllerian agenesis) in adolescent teens or two-sided labial/inguinal hernia with testes in children around prepubertal age. Our paper reports a case of CAIS in a 16-year-old woman with no menarche and 46,XY karyotyping. Gonadectomy results showed hyperplasia of Leydig cells. The current research encompasses the case report and the available knowledge to date on the understanding, diagnosis, treatment, and management of CAIS.

Keywords

For citations:

Morkos S., Al Qasem M., Aldam M., Bhotla H.K., Meyyazhagan A., Pappuswamy M., Iskandarani F., Kouteich K., Asoliman A. An exposition on complete androgen insensitivity syndrome and a case report. Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproduction. 2025;19(1):127-135. https://doi.org/10.17749/2313-7347/ob.gyn.rep.2025.539

Introduction / Введение

One of the wanted 46,XY karyotyped X-linked sexual differentiation disorders caused by anomalies in the receptor gene of androgen is known as androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS) [1–3]. Anomalies in the receptor lead to the disrupted transmission of androgen signaling to the target cells during the intra-uterine and post-natal phases, accounting for phenotypic variation from out-and-out feminization to masculinization based on the residual activity of the gene along with moderate features of infertility [1]. Every one in 20,000–100,000 live births accounts for AIS and constitutes nearly 80 % of sexual differentiation disorder people [4][5]. J.М. Morris first identified the syndrome in 1943 [6] and in 1989, anomalies in the exact locus, Xq11-12, on the Androgen Receptor (AR) gene were linked to the AIS phenotype [6–8].

Accordingly, AIS is categorized as complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS), mild androgen insensitivity syndrome (MAIS), partial androgen insensitivity syndrome (PAIS), and five grades based on androgen resistance severity in PAIS include [3][9]:

Grade 1: Normal female genitalia with androgen-dependent pubic/axillary hair at puberty.

Grade 2: Female phenotype with moderate clitoromegaly/posterior labial fusion.

Grade 3: Undifferentiated phallic motif intermediates between clitoris and penis with the presence of perineal orifice and labioscrotal folds in the urogenital sinus.

Grade 4: Predominantly male characteristics along with cryptorchidism/bifid scrotum, perineal hypospadias, and small penis.

Grade 5: Isolated hypospadias/micropenis.

Grade 4 and 5 forms of PAIS resemble MAIS; the only difference is the coronal hypospadias/scrotum with prominent midline raphe [10]. Some MAIS cases could alter spermatogenesis and fertility at puberty, irrespective of the usual gynecomastia and impotence [11][12].

Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome / Синдром полной нечувствительности к андрогенам

CAIS is commonly observed as an AIS manifestation due to mutation in the AR gene in 95 % of cases, with 70 % being inherited from mother and 30 % as de novo [13]. CAIS is typically characterized by a vagina with a short blind end, Wolffian duct-derived motifs like vas deferens, epididymides, seminal vesicles, and prone are absent along with the seldom presence of Müllerian duct-derived motifs [12]. An effective diagnosis of CAIS is the absence or scarce pubic and axillary hair development, irrespective of the regular breast development during puberty [9]. Early diagnosis can be made by amniocentesis (karyotype) contrary to ultrasound or clinical evidence seen at birth, such as external female genitalia [12][14]. The development of mono or bilateral inguinal hernia in female children is another diagnosis [15]. The National Institute of Health classifies CAIS as a 'rare disease' [16].

The paper highlights some aspects of CAIS, its genetics, diagnostics, and management. We have also recently discussed the case observed in our clinic along with some controversial aspects considering the findings from the basic research.

Epidemiology and etiology of androgen insensitivity syndrome / Эпидемиология и этиология синдрома нечувствительности к андрогенам

Though females with 46,XY karyotype are rare, the prevalence is registered as 4.1 per 100,000 female births through a Danish study group [17]. However, molecular testing data suggests the prevalence of AIS is 1 in 40,800 or 1 in 99,000 males [2][18], carrying mutations in the AR gene contrary to the receptor's residual function. Due to the extreme variability of PAIS and MAIS phenotypes, a precise prevalence is unavailable [2]. Irrespective of varying phenotypes, CAIS and PAIS have similar backgrounds in pathophysiology, endocrinal, and genetic studies [9]. Loss-of-function mutation in the coding sequence of the AR gene causes AIS due to androgen hormonal resistance and dysfunction, leading to infertility in 46,XY males despite adequate testosterone production and proper testes functioning.

Clinical manifestations / Клинические симптомы

The primary presentation of CAIS females includes normal external female genitalia with undescended testes due to complete androgen resistance. Primordial testes are found in the abdomen during the fetal stage around the seventh week of gestation as the sex-determining region Y (SRY) is present and produces ineffective testosterone due to the presence of AR anomalies in target cells, resulting in the absence of other male genitalia [13][19]. Even internal female genitalia are nonexistent due to the production of an anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) by abdominal testes to hamper proximal vagina, cervix, and uterus development [19]. However, distal structures of the vagina are intact with shorter blind ending as it is not under AMH influence [20][21]. CAIS females attain puberty later or slower than the normal female population, irrespective of breast and adipocyte development due to estradiol derived from testosterone peripheral aromatization. Androgen insensitivity leads to no or rare pubic and axillary hair [22].

CAIS cases are taller than healthy females due to the Y chromosome intervening in the growth stature. Hormonal analysis depicts higher luteinizing hormone (LH) with normal follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), which may be due to the regulation of gonadal inhibin [23][24]. Basal testosterone levels are higher than those of normal females and are within the normal range for males [10][24]. It is suspected, according to age, neonates are characterized by external female genitalia when prenatal results showed 46,XY karyotype in a girl child along with other characteristics like inguinal hernia, swollen labia with testes, and amenorrhea during puberty [24].

Molecular biology of androgen receptor / Молекулярная биология андрогеновых рецепторов

Androgen is one of the major players in reproductive and non-reproductive function in males till the end [25], it is responsible for the proper development of the internal and external genitalia in the fetal stage. The growth and functioning of all male genital systems and the spurts of secondary sexual character during puberty are all controlled by androgen in both genders. Adults require androgen to maintain the musculoskeletal system's health, spermatogenesis, and virility [24].

The action of androgen relies on the direct interaction with AR encoded by the AR gene present in the long arm of the X chromosome at the q11-13 locus [26]. AR belongs to the nuclear receptor superfamily consisting of 920 peptides of 110 kDa molecular mass arranged in eight exons and seven introns with designation as nuclear receptor superfamily 3, group C, member 4 (NR3C4). AR is a mono-stranded polypeptide with four prime structural domains [3][9][19][21][27]. The N-terminus comprises 538 amino acids encoded by exon 1 containing activation function-1 (AF-1) region, the transactivating domain regulating and initiating the target genes transcription contributing to the final 3-dimensional receptor structure [27]. Exon 2 and 3 (amino acids 558-617) encode the DNA-binding domain (DBD), largely composed of cysteine residues binding through a disulfide bridge to two zinc atoms to form the "Zing finger" – the tertiary structure to interact with the hormone response elements (HREs). It is followed by the hinge domain, which is responsible for the structural changes caused by androgen. Next is the ligand-binding domain (LBD) comprising of 646–920 peptides constituting the exons 4 to 8 necessary for androgen binding, coactivation transcription factors and AF-2, androgen hormone interaction along with heat shock proteins interaction in the cytoplasm for AR nuclear translocation [21][28].

The AF-1 (N-terminal) and AF-2 (C-terminal) domains interact and stabilize the association between the receptor and its ligand to slow dissociation. Ideally, the AR stays in the cytoplasm to form a complex multimer with the heat shock proteins and dissociates after interacting with androgen in the nucleus. The AR-androgen complex binds to the HREs in the nucleus to regulate gene transcription [29]. 2/3rd of the mutations in AR originate from the germline through inheritance from an asymptomatic mother, and the remaining are de novo or somatic mutations that cause CAIS [30]. About 1/3rd of the de novo mutations are estimated to be seen in the postzygotic stage, explaining the variability in the phenotype of the subjects with same genetic alteration. Impaired coactivators or post-ligand binding components can also lead to AIS phenotype and biochemical profiling without mutation in the AR gene [29].

AR gene mutation results in altered or deficit synthesis of AR or nonfunctional receptors to bind [31]. About 900 AR mutations are registered to induce AIS, widely categorized under four major mutations: 1) single nucleotide variation producing stop codon or amino acid substitution; 2) frame shift mutation due to deletion or insertion; 3) complete or partial gene deletion; 4) altered splicing of RNA (intron mutations). Mutations in the N-terminus mostly result in premature stop or frameshift aberration, seen mostly in CAIS [32][33]. AR activation is greately impaired due to mutations in the DBD, though 2 studies showed that a mutation in DBD doesn't hinder AR [34][35]. Alterations in the hinge region also significantly inhibit AR activity due to its flexibility or absence of gene sequence region [36]. LBD region is largely highly mutational, leading to CAIS and PAIS, impeding AR functioning such as its stability binding strength with ligands and other coactivators [24].

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis / Диагноз и дифференциальная диагностика

Hormonal profiling of testosterone, FSH, and LH immediately after birth. PAIS cases show higher levels of post-natal gonadotropin and testosterone levels compared to CAIS, as the levels of gonadotropins depend on androgen [37]. Testosterone synthesis in children is assessed through stimulation assay with the human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) after 72 hours to measure androstenedione, dihydrotestosterone (DHT), and testosterone in the serum. As in adults, measuring the basal levels of hormones reveals androgen insensitivity with normal to elevated total testosterone and higher LH [2]. Peripheral testosterone aromatization increases estrogen levels compared to the male reference index but remains within the normal range for reproductive age women [3].

Primary amenorrhea is the main reason to differentially diagnose as deficiency of any enzyme in the pathway of testosterone biosynthesis or LH receptor alteration can cause amenorrhea. Likewise, the presence of Leydig cell dysfunction in 46,XY women increases gonadotropin, causing delayed puberty-related development and secondary sexual characteristics dissimilar to CAIS. Conditions like Mayer–Rokitansky–Kuster–Hauser syndrome (46,XX) should be differentiated as the primary characteristics include primary amenorrhea and female external genitalia like in AIS [38].

PAIS genetic and phenotypic differences could result in differential diagnoses with many diseases like androgen synthesis defects and gonads dysgenesis disorders (Partial, mixed). CAIS and PAIS are differentiated from 17-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 5α-RD2 deficiency [2]. Genetic testing followed by histopathology of the removed gonads confirms AIS diagnosis.

Management and therapeutics / Ведение пациентов и терапия

CAIS is managed by properly collaborating with surgeons, gynecologists, endocrinologists, and psychologists to maintain child well-being. Patient management is imperative, including counseling of the family, gender assignment, and improving functional status relating to gonadectomy timing to avert tumorigenesis. If CAIS is established during infancy, gonadectomy must be considered after interviewing with parents, and estrogen hormonal therapy is applied to attain puberty or postpone gonadectomy until early adulthood in case of low chances of childhood gonadal malignancy development [2][39].

This leads to spontaneous puberty with appropriate growth spurt and mammary development. After puberty, gonadectomy is performed with hormone replacement therapy (HRT) prior to average menopause age to boost the secondary sexual characteristics, physiological growth spurt for proper bone mass, and social and sexual well-being achievement.

CAIS is surgically managed by dilatating the vagina or vaginoplasty in a few cases to ensure well-being and normal sexual functioning. So far, no population-specific rules are available for dosage, route, and type of HRT in women with CAIS. However, micronized 17-β-estradiol is administered orally or transdermally as gel/patches [40][41]. CAIS women are administered 50 mg/day of testosterone as a substitute for estrogen therapy [2].

Few studies showed that testosterone administration prevents virilization and boosts sexual life as the metabolites of testosterone interact with receptors other than AR [42]. This treatment is associated with significantly less high-density lipid cholesterol, generally less lipid profile, and a significant increase in body mass index (BMI) [43]. CAIS women without gonadectomy procedures receive HRT, considering the residual activity of the testes, to balance the basal androgen to estrogen production. Parents diligently interview PAIS infants to assign gender; if assigned as male, androgen HRT is applied during puberty with corrective surgery for hypospadias and cryptorchidism at > 3 years of age. Mammoplasty is carried out to reduce gynecomastia in pubertal age along with baring tumors, though men with PAIS have lower tumor incidence [44]. In the case of female sex assignment, genitoplasty with gonad removal and estrogen replacement therapy is provided to induce puberty [2].

Growth, bone, and psychological repercussion / Развитие организма, костной системы и психологические последствия

CAIS individuals with persistent gonads show pubertal characteristics at a normal age, demonstrating estrogen-stimulated growth in androgen absence. Estrogen interacts with growth hormones like insulin growth factor 1 (IGF1). Hormones from testes like insulin-like 3 (INSL3) modulate osteoblastic and bone mineralization [45–47]. CAIS women show lower peak bone mass compared to unaffected, irrespective of estrogen source, and may lack androgens direct action on the bones [48][49]. Psychologically, boys with PAI show worse clinical outcomes compared to other disorders of sex development (DSD) XY [50]. Distress affecting all aspects of life is observed during the adolescent-to-adult transition period in individuals and the family [51]. Removal of gonads leads to jeopardized sexuality, causing severe distress in CAIS women [2][48][49].

Case report / Клинический случай

We reported a case of 16-year-old phenotypic women with the concern of primary amenorrhea with no history of cyclic abdominal pain and urinary symptoms, along with no familial history. Clinical investigation revealed no axillary and pubic hair with normally developed breasts. Swollen groin was present bilaterally with external genitalia of females distinguished by the blind end. The pelvic sonogram showed the absence of uterus and ovarian follicle tissue. It mandated magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing the presence of inguinal gonads in both left and right positions, weighing 26.24 grams, sized 55×25×20 mm and 50×23×20 mm, respectively, with a glistening smooth surface. No cords were observed in the testes. One testis serial sectioning 17×14×45 mm showed a solid cream nodule at one polar end and a testicle-like structure sized 18×12×12 mm, implying a ligament part. The testis was wrapped in layers of tissue.

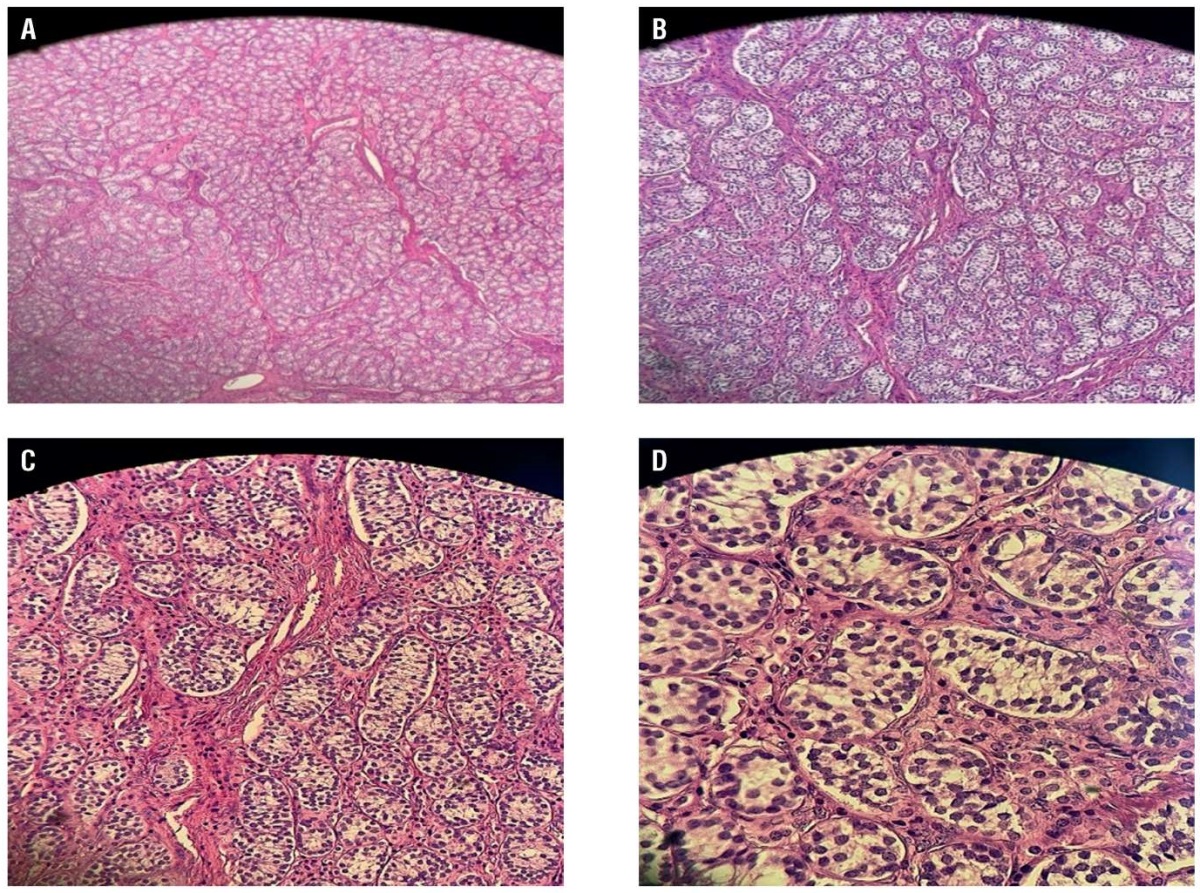

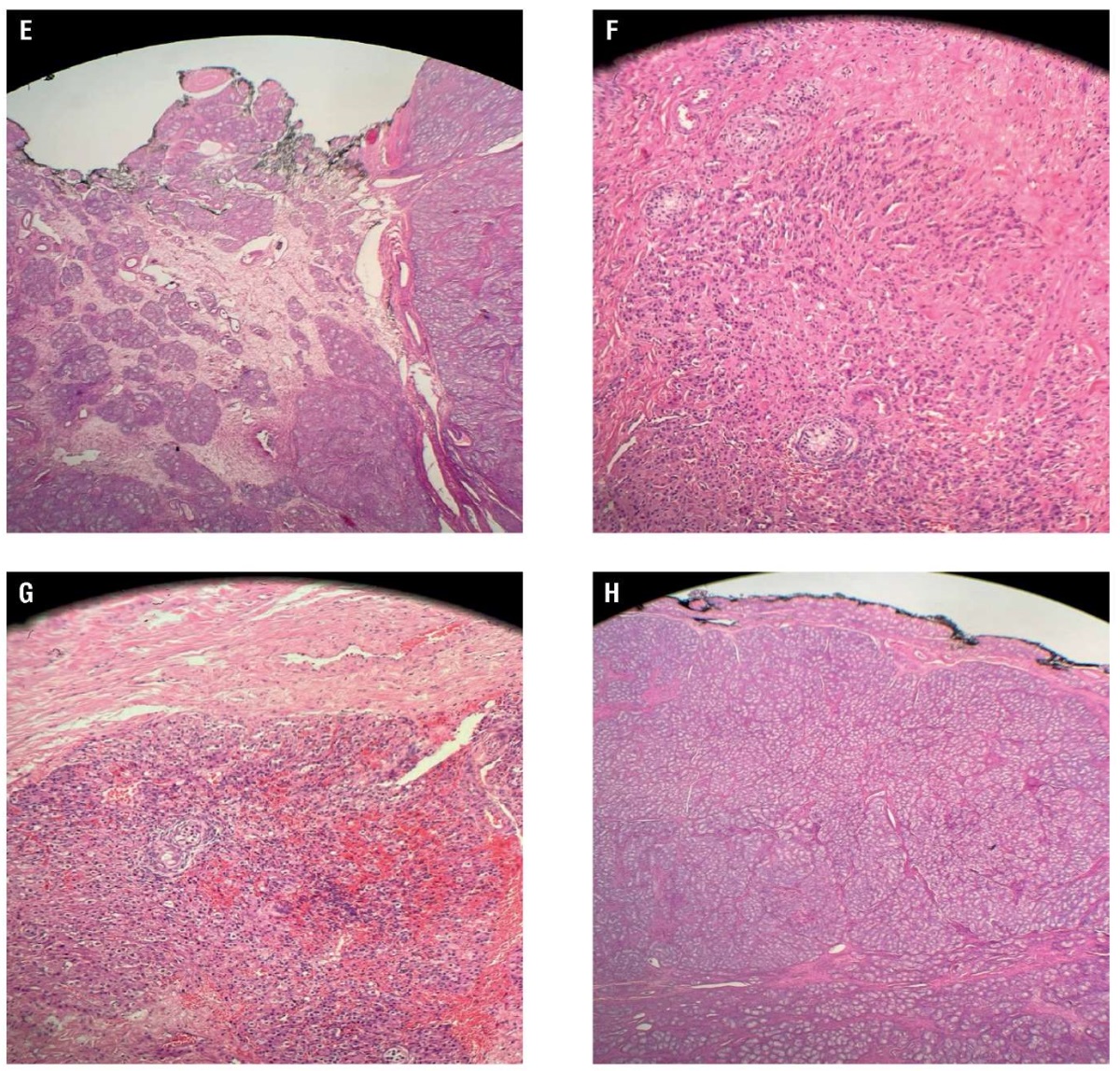

In contrast, the other testis revealed an atrophic testicle measuring 18×16×38 mm in serial sectioning with a pale nodule in the polar end sized 20×15×12 mm, suggesting its origin from the testicle. Genetic studies including karyotyping are carried out by peripheral blood DNA extraction, confirming 46,XY phenotype rejecting the Mayer–Rokitansky syndrome and verified as AIS. The parents and the patient are duly counseled on managing and diagnosing the clinical situation. The histological investigation disseminated atrophic seminiferous tubules and hyperplasia of Leydig cells with no spermatozoa in both testes. Testis 1 (Fig. 1) showed the presence of a spermatic cord with no vas deferens. Parenchymal tissue in the testis was in the surgical margin with circumscribed fibromuscular stroma in one pole as a ligament component. Testis 2 (Fig. 2) had features similar to vas deferens. Fibrous septae traversing and separating seminiferous tubules were present in both testes with no intro-tubal germ cell neoplasia. The examination showed bilateral testicular gonads with atrophic testes and hyperplasia of Leydig cells in a phenotypic woman with 46,XY karyotype. The patient was mentally distressed and attempted to end her life after diagnosis.

The above histologic section shows two rudimentary testes, in which both specimens show atrophic seminiferous tubules and Leydig cell hyperplasia. No spermatozoa are seen within both specimens. Testis 1 (Fig. 1A–1D)also show part of a spermatic cord, but no vas deferens are observed. Towards one pole, there is a well-circumscribed fibromuscular stroma, with preserved part of a ligament, which could represent a rudimentary round ligament. Testis 2 (Fig. 2E–2H) shows similar features and a vas deferens. Both testes show fibrous traversing septae that separate the seminiferous tubules. No intra-tubal germ cell neoplasia (ITGN) or malignancy is detected. These features are in keeping with our CAIS presentation.

Figure 1. Representative photomicrograph of a specimen from a right inguinal mass removed from a 16-year-old female with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome showed the following: A – testis with no vas deferens; B – hyperplasia of Leydig cells; C and D – the tumour cells were round and grew diffusely, the cytoplasm was strongly eosinophilic, and the nuclei were round with little atypia (haematoxylin and eosin).

Рисунок 1. Микрофотография образца правого пахового образования, удаленного у 16-летней девушки с синдромом полной нечувствительности к андрогенам: A – отсутствие семявыносящего протока; B – гиперплазия клеток Лейдига; C и D – округлые опухолевые клетки с диффузным ростом, резко эозинофильная цитоплазма, округлые ядра с небольшой атипией (окраска: гематоксилин и эозин).

Figure 2. Representative photomicrograph of a specimen from a left inguinal mass removed from a 16-year-old female with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome showed the following: E – testis with no vas deferens; F – hyperplasia of Leydig cells; G and H – the tumour cells were round and grew diffusely, the cytoplasm was strongly eosinophilic, and the nuclei were round with little atypia (haematoxylin and eosin).

Рисунок 2. Микрофотография образца левого пахового образования, удаленного у 16-летней девушки с синдромом полной нечувствительности к андрогенам: E – отсутствие семявыносящего протока; F – гиперплазия клеток Лейдига; G и H – округлые опухолевые клетки с диффузным ростом, резко эозинофильная цитоплазма, округлые ядра с небольшой атипией (окраска: гематоксилин и эозин).

Discussion / Обсуждение

The CAIS individuals are managed with loads of difficulty right, from assigning gender, gonadectomy timing, HRT, and sexual functioning to reproduction [52][53]. Bruce Gottlieb, PhD, and Mark A. Trifiro, MD, published as authors in GeneReviews® that supportive laboratory findings for CAIS would be: 1 – evidence of normal or increased synthesis of testosterone by the testes; 2 – evidence of normal conversion of testosterone to DHT; 3 – evidence of normal or increased LH production by the pituitary gland [54]. C. Bouvattier et al. (2002) stated that in CAIS, but not in PAIS, there is a possible reduction in postnatal (0–3 months) surge in serum LH and serum testosterone concentrations [37].

Our case illustrates the need for a multidisciplinary team to obtain satisfactory output. Our 16-year-old case showed primary amenorrhea with swollen groin, well-developed mammary glands due to peripheral aromatization of androgen to oestradiol, and less to no axillary/pubic hair due to androgen insensitivity, implying CAIS condition. MRI studies showed a lack of structures derived from Mullerian hormones like the uterus, fallopian tube, ovaries, and upper region of the vagina. Ultrasound showed the presence of inguinal gonads. Testes release Mullerian inhibiting hormones leading to agenesis of Mullerian structures with the presence of lower vaginal structure as derived from urogenital sinuses in the embryological stage [55]. CAIS differs from Mayer–Rokitansky syndrome as it possesses a Mullerian structure with XX karyotype and primary amenorrhea [56]. CAIS is generally confirmed by identifying alteration in the AR gene but couldn't be performed in our patient due to non-availability, and timely gonadectomy was carried out as she had already attained secondary sexual manifestations. However, histological investigation showed hyperplasia of Leydig cells. CAIS patients are at risk of developing malignancies in general related to the testis and usually higher in post-puberty [53][57][58]. Patient’s secondary sexual characteristics, bone, and cardiovascular health are good following bilateral gonadectomy and HRT. Oral estrogen replacement therapy is considered a recommendation till menopause to obtain satisfactory results.

Conclusion / Заключение

A rare case of complete androgen insensitive syndrome is reported in an adolescent woman, and we have documented our encounter with the case report that came to us with the complaint of primary amenorrhea along with palpable gonads in the inguinal region, 46,XY karyotype. In general, gonad removal can be delayed till puberty. AR is the key player in differentiating gender in utero, leading to many effects. To achieve the optimized health status defined by the World Health Organization, the CAIS women require a multidisciplinary approach to deal with the rarity of DSD in both mental and physical aspects. The clinical problem of CAIS suppresses the life quality of patients, leading to self-destruction thoughts. Hence, correct AIS management must be done with a multidisciplinary group of physicians to counsel and support patient as well as family members properly for positive outcomes for patient's future. The government can make comprehensive genetic screening available for newborns to tackle future psychological problems associated with DSD identified at older age.

References

1. Hughes I.A., Houk C., Ahmed S.F., Lee P.A.; LWPES Consensus Group; ESPE Consensus Group. Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91(7):554–63. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2006.098319.

2. Delli Paoli E., Di Chiano S., Paoli D. et al. Androgen insensitivity syndrome: a review. J Endocrinol Invest. 2023;46(11):2237–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-023-02127-y.

3. Hughes I.A., Davies J.D., Bunch T.I. et al. Androgen insensitivity syndrome. Lancet. 2012;380(9851):1419–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60071-3.

4. Costagliola G., di Cosci M.C.O., Masini B. et al. Disorders of sexual development with XY karyotype and female phenotype: clinical findings and genetic background in a cohort from a single centre. J Endocrinol Invest. 2021;44(1):145–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-020-01284-8.

5. Peng Y., Zhu H., Han B. et al. Identification of potential genes in pathogenesis and diagnostic value analysis of partial androgen Insensitivity syndrome using bBioinformatics analysis. Front Endocrinol. 2021;12:731107. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.731107.

6. Morris J.M. The syndrome of testicular feminization in male pseudohermaphrodites. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1953;65(6):1192–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(53)90359-7.

7. Brown C.J., Goss S.J., Lubahn D.B. et al. Androgen receptor locus on the human X chromosome: regional localization to Xq11-12 and description of a DNA polymorphism. Am J Hum Genet. 1989;44(2):264–9.

8. Brown T.R., Lubahn D.B., Wilson E.M. et al. Deletion of the steroid-binding domain of the human androgen receptor gene in one family with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome: evidence for further genetic heterogeneity in this syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(21):8151–5. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.85.21.8151.

9. Quigley C.A., De Bellis A., Marschke K.B. et al. Androgen receptor defects: historical, clinical, and molecular perspectives. Endocr Rev. 1995;16(3):271–321. https://doi.org/10.1210/edrv-16-3-271.

10. Melo K.F.S., Mendonca B.B., Billerbeck A.E. et al. Clinical, hormonal, behavioral, and genetic characteristics of androgen insensitivity syndrome in a Brazilian cohort: five novel mutations in the androgen receptor gene. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(7):3241–50. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2002-021658.

11. Pinsky L., Kaufman M., Killinger D.W. et al. Human minimal androgen insensitivity with normal dihydrotestosterone-binding capacity in cultured genital skin fibroblasts: evidence for an androgen-selective qualitative abnormality of the receptor. Am J Hum Genet. 1984;36(5):965–78.

12. Pizzo A., Laganà A.S., Borrielli I., Dugo N. Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome: a rare case of disorder of sex development. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:232696. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/232696.

13. Oakes M.B., Eyvazzadeh A.D., Quint E., Smith Y.R.. Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome – a review. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2008;21(6):305–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2007.09.006.

14. Stephens J.D. Prenatal diagnosis of testicular feminisation. Lancet. 1984;2(8410):1038. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91134-6.

15. Grumbach M.M., Conte F.A., Hughes I.A. Disorders of sex differentiation. In: Williams textbook of endocrinology. Eds. P.R. Larsen, H.M. Kronenberg, S. Melmed et al. 10th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 2002.

16. Singh S., Ilyayeva S. Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL), 2023 Feb 28.

17. Berglund A., Johannsen T.H., Stochholm K. et al. Incidence, Prevalence, diagnostic delay, and clinical presentation of female 46,XY disorders of sex development. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(12):4532–40. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2016-2248.

18. Boehmer A.L., Brinkmann O., Brüggenwirth H. et al. Genotype versus phenotype in families with androgen insensitivity syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(9):4151–60. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.86.9.7825.

19. Gulía C., Baldassarra S., Zangari A. et al. Androgen insensitivity syndrome. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22(12):3873–87. https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_201806_15272.

20. Dey R., Biswas S.C., Chattopadhvav N. et al. The XY female (Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome)-runs in the family. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2012;62(3):332–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-011-0112-x.

21. Batista R.L., Costa E.M.F., Rodrigues A.S. et al. Androgen insensitivity syndrome: a review. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2018;62(2):227–35. https://doi.org/10.20945/2359-3997000000031.

22. Gottlieb B., Pinsky L., Beitel L.K., Trifiro M. Androgen insensitivity. Am J Med Genet. 1999;89(4):210–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19991229)89:43.0.co;2-p.

23. Doehnert U., Bertelloni S., Werner R. et al. Characteristic features of reproductive hormone profiles in late adolescent and adult females with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome. Sex Dev. 2015;9(2):69–74. https://doi.org/10.1159/000371464.

24. Lanciotti L., Cofini M., Leonardi A. et al. Different clinicalpresentations and management in Complete Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome (CAIS). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(7):1268. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071268.

25. Mainwaring W.I. The mechanism of action of androgens. Monogr Endocrinol. 1977;10:1–178.

26. Verhoeven G., Swinnen J.V. Indirect mechanisms and cascades of androgen action. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1999;151(1–2):205–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00014-3.

27. Galani A., Kitsiou-Tzeli S., Sofokleous C. et al. Androgen insensitivity syndrome: clinical features and molecular defects. Hormones (Athens). 2008;7(3):217–29. https://doi.org/10.14310/horm.2002.1201.

28. Gobinet J., Poujol N., Sultan C. Molecular action of androgens. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;198(1–2):15–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00364-7.

29. Tyutyusheva N., Mancini I., Baroncelli G.I. et al. Complete Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome: from bench to bed. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(3):1264. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22031264.

30. Hiort O., Sinnecker G.H., Holterhus P.M. et al. Inherited and de novo androgen receptor gene mutations: investigation of single-case families. J Pediatr. 1998;132(6):939–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70387-7.

31. Brown T.R. Human androgen insensitivity syndrome. J Androl. 1995;16(4):299–303.

32. Gelmann E.P. Androgen receptor mutations in prostate cancer. Cancer Treat Res. 1996;87:285–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-1267-3_12.

33. Sack J.S., Kish K.F., Wang C. et al. Crystallographic structures of the ligand-binding domains of the androgen receptor and its T877A mutant complexed with the natural agonist dihydrotestosterone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(9):4904–9. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.081565498.

34. Lobaccaro J.M., Poujol N., Chiche L. et al. Molecular modeling and in vitro investigations of the human androgen receptor DNA-binding domain: application for the study of two mutations. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1996;116(2):137–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/0303-7207(95)03709-8.

35. Brüggenwirth H.T., Boehmer A.L., Lobaccaro J.M. et al. Substitution of Ala564 in the first zinc cluster of the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA)-binding domain of the androgen receptor by Asp, Asn, or Leu exerts differential effects on DNA binding. Endocrinology. 1998;139(1):103–10. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo.139.1.5696.

36. Greep R.O. Reproductive endocrinology: concepts and perspectives, an overview. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1978;34:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-571134-0.50005-3.

37. Bouvattier C., Carel J.-C., Lecointre C. et al. Postnatal changes of T, LH, and FSH in 46,XY infants with mutations in the AR gene. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(1):29–32. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.87.1.7923.

38. Griffin J.E., Edwards C., Madden J.D. et al. Congenital absence of the vagina. The Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85(2):224–36. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-85-2-224.

39. Hannema S.E., Scott I.S., Rajpert-De Meyts E. et al. Testicular development in the complete androgen insensitivity syndrome. J Pathol. 2006;208(4):518–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.1890.

40. Bertelloni S., Dati E., Baroncelli G.I., Hiort O. Hormonal management of complete androgen insensitivity syndrome from adolescence onward. Horm Res Paediatr. 2011;76(6):428–33. https://doi.org/10.1159/000334162.

41. Birnbaum W., Bertelloni S. Sex hormone replacement in disorders of sex development. Endocr Dev. 2014;27:149–59. https://doi.org/10.1159/000363640.

42. Reddy D.S. Testosterone modulation of seizure susceptibility is mediated by neurosteroids 3alpha-androstanediol and 17beta-estradiol. Neuroscience. 2004;129(1):195–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.08.002.

43. Auer M.K., Birnbaum W., Hartmann M.F. et al. Metabolic effects of estradiol versus testosterone in complete androgen insensitivity syndrome. Endocrine. 2022;76(3):722–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-022-03017-8.

44. Poujol N., Lobaccaro J.M., Chiche L. et al. Functional and structural analysis of R607Q and R608K androgen receptor substitutions associated with male breast cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1997;130(1–2):43–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0303-7207(97)00072-5.

45. Coutant R., de Casson F.B., Rouleau S. et al. Divergent effect of endogenous and exogenous sex steroids on the insulin-like growth factor I response to growth hormone in short normal adolescents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(12):6185–92. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2004-0814.

46. Perry R.J., Farquharson C., Ahmed S.F. The role of sex steroids in controlling pubertal growth. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2008;68(1):4–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02960.x.

47. Ferlin A., Selice R., Carraro U., Foresta C. Testicular function and bone metabolism – beyond testosterone. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9(9):548– 54. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2013.135.

48. Döhnert U., Wünsch L., Hiort O. Gonadectomy in Complete Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome: why and when? Sex Dev. 2017;11(4):171–4. https://doi.org/10.1159/000478082.

49. Tack L.J.W., Maris E., Looijenga L.H.J. et al. Management of gonads in adults with androgen insensitivity: an International Survey. Horm Res Paediatr. 2018;90(4):236–46. https://doi.org/10.1159/000493645.

50. Lucas-Herald A., Bertelloni S., Juul A. et al. The long-term outcome of boys with Partial Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome and a mutation in the androgen receptor gene. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(11):3959–67. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2016-1372.

51. Bouvattier C., Mignot B., Lefèvre H. et al. Impaired sexual activity in male adults with partial androgen insensitivity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(9):3310–5. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2006-0218.

52. Rasheed M.W., Idowu N.A., Adekunle A.A. et al. Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome with Sertoli cell tumour in a 27-year-old married woman: a case report. Afr J Urol. 2023;29(1):26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12301-023-00358-2.

53. Hughes I.A., Deeb A. Androgen resistance. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;20(4):577–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beem.2006.11.003.

54. GeneReviews®. Eds. M.P. Adam, J. Feldman, G.M. Mirzaa et al. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle, 1993. Copyright© 1993–2024.

55. Healey A. Embryology of the female reproductive tract. In: Imaging of gynecological disorders in infants and children. Eds. G.S. Mann, J.C. Blair, A.S. Garden. Springer Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012. 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-85602-3.

56. Valappil S., Chetan U., Wood N., Garden A. Mayer–Rokitansky–Küster–Hauser syndrome: diagnosis and management. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist. 2012;14(2):93–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-4667.2012.00097.x.

57. Cools M., Looijenga L. Update on the pathophysiology and risk factors for the development of malignant testicular germ cell tumors in Complete Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome. Sex Dev. 2017;11(4):175–81. https://doi.org/10.1159/000477921.

58. Chaudhry S., Tadokoro-Cuccaro R., Hannema S.E. et al. Frequency of gonadal tumours in complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS): A retrospective case-series analysis. J Pediatr Urol. 2017;13(5):498. e1–498.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2017.02.013.

About the Authors

S. MorkosUnited Arab Emirates

Simon Morkos, MD, Dr Sci Med, Prof.

Al Barsha, Khadaek Mohammed Bin Rashid, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

M. Al Qasem

Indonesia

Malek Al Qasem, MD, PhD

Al Karak 61710

M. Aldam

United Arab Emirates

Mustafa Aldam, MSc

Dubai

H. K. Bhotla

India

Haripriya Kuchi Bhotla, MD

Bengaluru, Karnataka 560029

A. Meyyazhagan

India

Arun Meyyazhagan, MD, PhD

Bengaluru, Karnataka 560029

M. Pappuswamy

India

Manikantan Pappuswamy, MD, PhD

Bengaluru, Karnataka 560029

F. Iskandarani

United Arab Emirates

Fadi Iskandarani, MD

Al Barsha, Khadaek Mohammed Bin Rashid, Dubai

K. Kouteich

United Arab Emirates

Khaled Kouteich

Al Barsha, Khadaek Mohammed Bin Rashid, Dubai

A. Asoliman

United Arab Emirates

Ahmed Asoliman, MSc

Al Barsha, Khadaek Mohammed Bin Rashid, Dubai

What is already known about this subject?

► Alteration of androgen gene causes androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS). Alteration results in jeopardized androgen signaling with 46,XY karyotype and infertility.

► Prevalence rate of 20,000–100,000 among live birth and classified as complete, mild and partial AIS.

► Generally, gonadectomy followed by hormonal replacement therapy is given during puberty.

What are the new findings?

► Reported an early case of AIS misdiagnosed as inguinal hernia by 16 years old.

► Peripheral cultural confirmed 46,XY karyotype rejecting Mayer–Rokitansky syndrome and confirmed AIS.

► Bilateral testicular gonads with atrophic testes and Leydig cells hyperplasia with 46,XY phenotype were detected. Mental distress and suicide attempt was observed after diagnosis.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

► Family history and symptoms history from primary amenorrhea to cyclic abdominal pain or urinary symptoms.

► Importance of сlinical investigation to assess axillary and pubic hair, breasts development.

► Bilateral swollen groin with external genitalia of females. Importance of pelvic sonogram, karyotype to confirm the absence of uterus and ovarian follicle tissue.

Review

For citations:

Morkos S., Al Qasem M., Aldam M., Bhotla H.K., Meyyazhagan A., Pappuswamy M., Iskandarani F., Kouteich K., Asoliman A. An exposition on complete androgen insensitivity syndrome and a case report. Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproduction. 2025;19(1):127-135. https://doi.org/10.17749/2313-7347/ob.gyn.rep.2025.539

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.